Spontaneous Human Combustion: A Brief History

Table of Contents

Mysterious Fires

Fire From Within

The Study Begins

Not So Spontaneous Combustion

SHC in Popular Fiction

The Scientific Approach

Modern Weirdness

Strange Associations and Interpretations

Science Marches On

Pig in a Blanket

Some Explanations... and Continuing Controversies

sources for the study

On July 2, 1951, the remains of 67-year-old Mary Reeser were discovered in her St. Petersburg, Florida apartment... and a strange sight it was.

Mrs. Reeser had apparently died due to an extremely localized fire; only she and the chair she was last seen sitting in had been consumed, though the heat from the fire had caused other damage in the one-room apartment. Of the chair, only charred coil springs remained. Of Mrs. Reeser, there was little more; her 170 pounds had been reduced to less than ten pounds of charred material. Only her left foot remained completely intact, still wearing a slipper and burnt off neatly at the ankle, otherwise undamaged. A lump of vertebrae was also found and, stranger still, a small object... which was later declared by the coroner to be her shrunken skull.

Mary Reeser's remains[Larger version here]

Mary Reeser's remains[Larger version here]

What could have burned Mrs. Reeser so fiercely without causing more damage to her surroundings? Experts interviewed by newspapers pointed out that a temperature of 2500 degrees is necessary for such a thorough cremation, and that a cigarette igniting her clothing would never have produced that temperature. The materials of the chair she sat in were only capable of a slow smolder, not an intense blaze. The electrical outlet had melted only after the fire had begun, so couldn’t be the source. An FBI pathologist tested for gasoline and other accelerants; there were none. Even lightning had been considered, but there had been none in St. Petersburg that night.

Months after the occurrence, the Chief of Police and the Chief of Detectives signed a statement attributing the fiery death of Mary Reeser to falling asleep with a cigarette in her hand, although this had already been shown to be an impossibility. The declaration was meant to publicly close the investigation... but some spoke of another possible cause; a very strange possible cause. Some believed that Mrs. Reeser was a fine example of Spontaneous Human Combustion.

Spontaneous Human Combustion... three simple words that convey a very bizarre possibility which many have argued to be absolutely true, and just as many have argued to be simply impossible. In the most basic sense, Spontaneous Human Combustion [“SHC“ from here on] describes a situation in which a person’s body is believed to catch fire and burn rapidly, being reduced to ashes in a matter of moments... with a point of ignition inside the person’s body. Strange though this idea may sound at first, a few hundred years ago – when the idea was first proposed – there were good reasons people would be inclined to believe such an event could happen.

First off, death by fire was hardly unusual: but it was well known that a tremendous amount of wood was required to reduce a human frame to mere ashes. On average, two cart-loads of wood were required to burn a criminal or martyr at the stake, and the same amount was needed to cremate a corpse. So the fact that people were being found burned down to ashes – including their bones -- on relatively undamaged floors, with no other obvious signs of fire damage within the area and often with undamaged limbs left behind, all implied a form of burning that had to be quite different from the fires used for purposeful cremation... a form of burning that might be supernatural. Hence when a man was found by his wife burned to death in bed in 1613, a pamphlet written about the event was entitled “Fire from Heaven burning the Body of one John Hitchell“.

As a second point, the very idea of combustion was not fully understood. For example, farmers knew that when hay was left in a pile under the right circumstances, it would catch fire on its own... but no one knew why. Some interesting ideas were put forward on the matter. In 1667, a man named Johann Joachim Becher proposed the idea that there existed a basic element that caused combustion; this element, later named Phlogiston, was released when an object burned; and the more Phlogiston in the object, the faster and more fierce the final combustion. It was also believed that the purpose of respiration in living beings was to exhale out Phlogiston that built up within their bodies... so, logically, there could be medical conditions that allowed Phlogiston to remain and build up within a living body, leading to a combustion.

Another early thought on the matter was that people became combustible by consuming combustible substances. In 1717, John Henry Cohausen repeated a case of a woman found reduced to ashes, a bit of skull, and a few digits, a story he claimed to have found in a book published in 1673. The proposed cause of this combustion was that the woman had been a heavy drinker, to the extent that, for three years, she had not consumed much else other than liquor... and this, presumably, made her body just as flammable as the alcohol she drank.

It was also suggested that some people were just remarkably unlucky. When the Countess de Bandi was found reduced to ashes in her room one morning in 1731, one of the first theories put foward claimed that her death was caused by a lightning strike that either traveled down the chimney, or snuck through the cracks in the window. The fact that no one had heard thunder was dismissed easily by stating that either everyone was in too deep a sleep, or because “there have been seen Lightnings and Fulmina without Noise; as one may very often observe.” [“Fulmina” is an old term for multiple lightning bolts. -- Garth]

The death of the Countess de Bandi of Cesana, Italy, sometime around April 4, 1731, is the primary event that led to the general investigation of these strange deaths.

The scene of her death was inspected by many people like the Reverend Giuseppe Biachini of Verona, Italy; but unlike others, Bianchini published a small book regarding his examinations of the room and remains, and his thoughts regarding what had happened. The Countess’ remains had been found on the floor of her room, halfway between her bed and the window, and consisted of a pile of ashes, two undamaged lower legs, and a calcined section of her skull lying on the ground between the legs.

To Bianchni’s imagination, this suggested but one possibility... that the Countess had been caught completely off guard by a sudden combustion while walking to the window. It had likely started somewhere in her lower abdomen, and burned so fiercely that her body was reduced to ashes as she was still standing; after which, her remaining skull fell straight down through the space her body had previously occupied to land between the undamaged remains of her lower legs.

Bianchini speculated that the initial ignition was somehow caused by the “effluvia” -- gases and waste -- within the Countess’ stomach and intestines igniting, perhaps assisted by vapors from an alcohol bath the Countess may have taken the night previous (she was in the habit of doing such when feeling ill). The arguments Bianchini put forward were to last for nearly two-hundred years, becoming the classic criteria for proving an abnormal internal source for certain fire deaths. Bianchini’s criteria, as he saw it in the case of the Countess and some of the other short cases he quoted, were:

- That a flame from any candle, lamp, or cooking fire could not possibly consume a human body to the great extent that is seen in these cases (especially the reduction of the bones to ashes).

- That under normal circumstances other objects in the area of the bodies should have also caught fire, but the flames seem to have unnaturally confined themselves to just their human victims.

- That most commonly in these cases, the torsos are destroyed but outer limbs are not; this is just opposite to damage caused by normal fire deaths in which limbs are typically destroyed before the torso is.

- The common presence of undamaged limbs is likely due to a fire that starts within the torso area of the body, and that runs out of fuel before reaching to the tips of the extremities.

- These fires must occur and spread extremely fast, for victims of it never appear to have resisted it... so death and burning must have been near instantaneous; in short, these must have been violent and spontaneous combustions.

Bianchini's report and ideas did not gain immediate attention; but fourteen years later, in 1745, Bianchini's report was translated to English and presented in the London magazine Philosophical Transactions. This new translation was presented by a Mr. Paul Rolli who also included two more examples of strange fire deaths: a pamphlet published in 1613 about a man named John Hitchell, and the contents of two letters from 1744 regarding a woman named Grace Pett. The Philosophical Transactions counted a large part of the professors, scientists, and doctors of Europe among its audience... so thanks to Rolli's re-presentation of Bianchini's report and study of the Countess' death, Bianchini's ideas regarding internal combustion became widely known.

With this newfound interest, many of these scholars began to search for more cases of this unusual demise. This initial search was very general in nature; just about any incident involving an unusual fire was considered as possible evidence. Bianchini, for example, felt these fire deaths were likely closely related to the then popular reports of luminous humans... people whose bodies were said to glow or spark under particular circumstances. Bianchini felt that these unusual people were simply luckier than the ones who were being found incinerated!

Over the next fifty years or so, many more cases of these strange deaths -- historical and contemporary -- were documented and added to the picture. Bianchini’s theoretical ideas of internal combustion suggested the possibility that this strange form of death could be caught before it happened, if the right set of symptoms were observed. Of course, what these symptoms would be was a matter of guesswork, but from this guesswork came many reports of strange medical conditions presumed to be somehow related to the combustion deaths... events such as people injured or dying by vomiting or excreting flames, or reports that people in the 9th century sometimes cut off a hand or foot to prevent an invisible fire from spreading through themselves.

While some of the learned men took these newly reported oddities as absolute proof of the internal nature of the fires causing the strange deaths, others started to protest that perhaps the evidence in the deaths had been read wrong to start with. It was noted that in nearly all known deaths that fit Bianchini’s criteria for an internal combustion fire, there was actually an obvious external source of fire available -- a candle, a hearth, a pipe -- and that the victims were likely setting themselves aflame with these. Still, even these protests were hedged by an admittance that, under normal circumstances, an external source of fire would never be able to cause the extreme and controlled damage done by the fires in the deaths being examined.

Thus a new theory started to form to explain the bizarre fire deaths. This new idea was that normal human bodies would indeed be incapable of being burned to the extent of the reported combustion deaths... but the people being burned to ashes didn’t have normal human bodies. These people had, it was asserted, made themselves more flammable than normal, so that a small flame could easily set them violently aflame and consume them in a short time. This proposed condition, called preternatural combustibility, was most often believed to be caused by an old culprit... alcoholism. When a person drank an abnormally large amount of alcohol for an abnormally long amount of time, it was believed that their body’s tissues could become more and more saturated with the flammable fluids which, in turn, made even the normally un-burnable bones of these people become flammable.

The definitive statement of the theory of preternatural combustibility came in 1800 when Pierre-aimi Lair published his study of the strange fire deaths, entitled “On the Combustion of the Human Body, produced by the long and immoderate Use of Spirituous Liquors”. As the title shows, Lair was absolutely convinced that these deaths were caused by alcohol; and he hoped that by publishing his study, he might convince many people to alter their habits in regard to drinking themselves stupid.

Lair studied fifteen cases of these combustion deaths, and stated that his information might not be perfect; yet he came up with very definitive -- and incorrect -- criteria for preternatural combustibility:

- All victims had made immoderate use of spirituous liquors.

- It only happens to women.

- All were far advanced in age.

- All were lit by outside sources of fire.

- In most cases, some extremities were left behind un-burned.

- Water sometimes boosted the fire rather than extinguished it.

- The fires mostly confined their damage to their victims.

- The fires reduced bodies to ashes and a stinking, penetrating soot.

Lair himself admitted that these criteria were likely not written in stone... they simply applied well to most of the fifteen cases he had considered. Several of the cases he looked at did not fit his criteria; but these were quietly ignored. Soon, Lair’s not-so-perfect list of criteria was being treated as unquestionably correct by supporters of preternatural combustibility.

Over the next one hundred years or so, preternatural combustibility as the cause for the strange fire deaths was to be accepted and argued for as much as the theory of internal combustion, by now renamed to “spontaneous human combustion”; and soon this debate was to become a public one.

Up to 1834, the idea that the strange fire deaths were being caused by either internal combustion or preternatural combustion had merely been a debate in journals aimed for a relatively small number of educated gentlemen. In that year, however, popular author and Royal Navy Captain Frederick Marryat [1792-1848], published his book Jacob Faithful, in which the lead character describes his mother’s death by preternatural combustibility.

It’s clear from the text of the novel that Marryat must have read Pierre-aimi Lair’s study of the strange deaths, for the circumstances and demise of Jacob’s mother in the novel is a picture perfect version of Lair’s proposed preternatural combustibility -- she was old, intemperate, and fat enough that she had only rarely left her bed in the past two years. Though the unusual death of this background character doesn’t seem to have raised much of a public stir at the time, it was probably the first mention of these deaths and the debate about their causes that was presented to a larger group of readers in a popular fiction story. About twenty years later, spontaneous human combustion was once again presented in a popular writer’s work; but this time, it was not allowed to sneak by quietly.

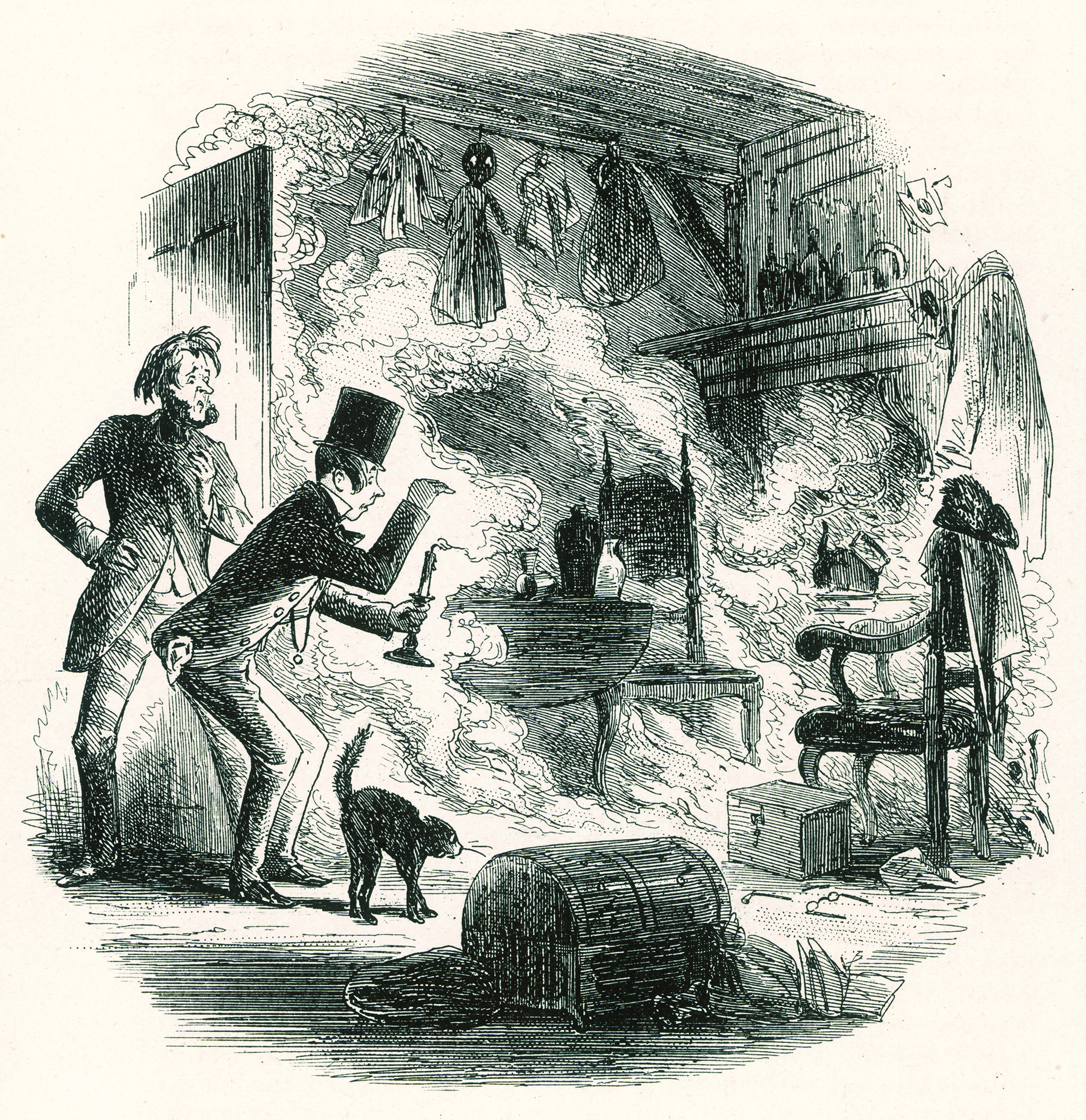

Mr. Krook meets his end in Dickens'Bleak House [Larger version here]

In 1852, famous author Charles Dickens used spontaneous human combustion as a device to kill off a character in his novel Bleak House. Dickens had researched the subject of these strange deaths a little, and modeled Mr. Krook’s demise on the detailed account of the Countess Cornelia di Bandi’s death published by Giuseppe Bianchini in 1731. In the novel, the first sign that something was not right was a strange fatty soot that was floating in the air of the house Krook occupied along with other tenants. Next, the lead characters of the story found a nauseating, yellowish, oily substance on the inside windows of the house. A short time after this discovery, the lead characters went to Mr. Krook’s room downstairs for a pre-scheduled meeting, but found something wrong... his room was full of strange smoke, and where Mr. Krook was last seen standing a few hours earlier was what is described as a looking like “the cinder of a small charred and broken log of wood sprinkled with white ashes;” Mr. Krook’s mortal remains.

It was an exciting way to kill off a villainous drunkard, but it brought a sharp response from Dickens’ friend, George Henry Lewes, who was then the head editor of The Leader. The main gist of Lewes' complaints -- published as editorials in his newspaper, and later in private letters to Dickens -- was simple; Lewes felt that the idea of spontaneous human combustion had already been completely disproven by the scientific minds of the day, and that by using this as a device within his story, Dickens was guilty of spreading a false and scientifically incorrect idea to a large audience that would now start to believe it could occur. Dickens’ response in the introduction of the completed volume of Bleak House, released in 1853, was straight to the point... he felt he wasn’t spreading a falsehood, and proceeded to quote more recent occurrences of the strange fire deaths. In a private letter to Lewes, not published publicly until 1955, Dickens had made his position even clearer; essentially, he states that while human combustions may or may not be spontaneous, the strange fire deaths had occurred, as evidenced by the numerous reports. Krook’s death in his novel was factually correct in description of what was known of these deaths to date, and he, as author, offered no other explanation for the event than would have been voiced by those examining it, whether or not that opinion would be scientifically valid.

As it turned out, Lewes was absolutely right; popular belief in the occurrence of spontaneous human combustion and preternatural combustibility were indeed greatly boosted by Dickens’ work... though, ironically, this may have been more due to the publicity Lewes’ letters gave to Dickens’ novel. At the same time, Lewes was also correct in stating that the scientists of his day for the most part no longer believed in the possibility of either spontaneous human combustion or preternatural combustibility.

Lewes’ opinion was mostly informed by the details of the death of the Countess of Goerlitz in Darmstadt in 1847, which resulted in a number of inquiries and experiments. The Countess had been found dead in her room on the evening of June 13, 1847, her head and upper body charred and blackened, her writing-desk smoldering a few feet away from her and another small fire smoldering in an ottoman much further away. Dr. Graff, the first doctor to observe the scene, immediately declared it a case of spontaneous human combustion... but the Countess’ husband was not fully convinced, nor were the police inspecting the matter. A fuller examination of the death was called for and a number of doctors and professors from the Hessian Medical College performed an autopsy, with the result that even Dr. Graff stated the case was not an occurrence of spontaneous human combustion, as the examination proved that all of the damage to the Countess’ body could have been caused by radiant heat from the burning desk. In fact, it was further determined that she had been murdered, either by strangulation or a blow to the head, and that the fire was an attempt to cover this fact up... and when some of the Countess’ missing jewelry turned up in association with the only servant who was in the house at the time of her death, and the facts were laid out, the servant made a full confession to the murder. People who didn’t believe in spontaneous human combustion, Lewes included, absolutely loved the news.

However, despite the how the matter ended, the main reason the Countess’ death was ruled as not being caused by spontaneous human combustion was that her death didn’t fit either Bianchini’s or Lair’s criteria for such deaths... the Countess was not an intemperate drinker, not of an advanced age, and, most importantly, had not been reduced to a pile of ashes. For these reasons alone other explanations were sought; and when the doctors and professors involved took the moment in the spotlight to state that they all felt that spontaneous human combustion was completely impossible, they failed to state why they felt it was impossible (Dr. Graff, by the way, was the only one who still stated that spontaneous human combustion might be possible). But it was a fact that the strange fire deaths had happened... and if these weren’t being caused by spontaneous human combustion or any other scientifically impossible process, then the problem became a matter of determining a scientifically acceptable way for these deaths to occur.

What neither Lewes nor the learned men from the Hessian Medical College knew was that a possible scientific explanation for the strange fire deaths had been proposed nearly seventy years previous to the publication of Bleak House in 1853.

The scientifically possible cause for the strange fire deaths, proposed at least as early as 1783, was the idea that the victims’ own body fats were enough to feed the fire consuming them, if their clothes acted as a wick for the flame.

In candles, the wick itself is not what produces a flame, even though it is what is first lit; shortly after the wick is lit, the wax below the flame becomes fluid enough that it gets sucked up through the porous wick to where the flame is... and from then on, the wick only burns when the wax gets too low to be carried up to the flame. When the wick burns low enough again, the liquid wax is once again drawn up and used as fuel for the flame. More than once, it was proposed that if a person’s clothes caught fire, then the cloth could soak up body fats from the tissues it contained, burning the body first, and burning the clothing second. If true, this could explain the selective nature of the fires in these strange deaths; the major parts of the bodies consumed would generally be the parts covered by clothing that could absorb liquid fat... and most of these fats would be in the victims’ torsos, the very part most commonly reduced to ash.

Protests against this idea were quick to be made by the both supporters of the internal combustion theory and supporters of the preternatural combustibility theory. The main arguments made against the “candle effect” (as it came to be known) was that such a fire would never be hot enough to break down a body (and certainly not the bones!); that said fire would burn slow enough that any fool, even drunk, would have a reasonable chance to extinguish it; and lastly, that plenty of people died of burns caused by their clothing catching fire, but very few turned up as a pile of ashes... so the flames in the strange fire deaths had to be something very different from the sort of common flames that burning clothes provided.

But as the 19th century proceeded, so did the scientific understanding of burning and combustion... and with it, new answers for some of the questions surrounding the strange fire deaths, as well as evidence that questioned the proposed criteria for both internal combustion and preternatural combustibility.

The first problem was that as more and more cases of these strange fire deaths were found, largely due to an increased number of people specifically looking for them, it became clear that victims didn’t necessarily have to be women, old, or drinkers... in short, most of Lair’s proposed criteria about who victims would be was actually wrong.

Another problem was that new evidence brought into question Bianchini’s assumption for a sudden, violent, combustion in the strange fire deaths. In 1888 Alexander Morrison, an old soldier, was found incinerated in a hayloft in Aberdeen, Scotland. Despite being literally converted to ash, the features of his calm, sleeping face were still clearly visible; this led the investigating physician, Dr. J. Mackenzie Booth, to look into some of the earlier deaths of this sort, and he reached the conclusion that in almost all cases the victim had not resisted the fire that consumed them. This fact had been noticed before, and was interpreted by Bianchini in his study of the deaths as proof that the strange fires had consumed their victims almost instantly. Dr. Booth reached a very different conclusion from the same evidence: he felt the reason the victims didn’t fight the fires was that the victims were dead before their bodies began to burn. These deaths were likely due to suffocation, often helped along by being too drunk to respond to the fire that killed the victims... and the fires could take their own sweet time destroying the victims’ remains.

Other criteria started to be questioned as well; for example, since these deaths now appeared to always have some form of external fire involved, the observation that they occurred more in the winter than the summer became simple to explain... more people spend time near fire in the winter than in the summer. In addition, since women’s work in homes and businesses typically involved using fires to cook, the reason more women seemed to have suffered from these strange deaths could be easily explained as due to this increased exposure to fire.

The next problem for theorists of spontaneous combustion and preternatural combustibility is that, during the 19th century, several of these strange combustion deaths were claimed to be witnessed in progress, and the victims were quickly investigated in regard to testing Bianchini and Lair’s proposed criteria... and, not surprisingly, the criteria was brought into question. The most famous of these events was that witnessed on May 12th, 1890, by Dr. B.H. Hartwell of Ayer, MA., in the United States. Called to the location of a deceased -- but still burning -- woman, he saw the body in full combustion, flames licking upwards of fifteen inches from it. Dirt was shoveled onto the body to stifle the flames. The woman, 49 years of age, of good health, active lifestyle, and not prone to drink, had been burning a pile of roots when somehow she had accidentally set her clothes aflame. The event happened after a rainfall, and the fire did not consume the leaves or other matter under the woman’s body... so, just by setting her clothes on fire, she had not only been killed but also set well and truly aflame, burning of just what fuel her own body supplied.

Dr. Hartwell clearly stated that he felt the fire was caused by a wick effect of the woman’s body fat being sopped up and burned through the clothes, and even mentioned another instance of which he knew wherein an elderly woman who fell during the night with an oil lamp set the straw matting of her floor alight; she was found burned to death in the morning, but the fire that had killed her had extinguished itself after using all the oxygen in the room, leading to very little damage otherwise. Yet, given these observations, Hartwell still found it hard to believe that a normal human body could simply burn as he witnessed... so his final explanation fell into the category of preternatural combustibility, with his belief that some people just have fat which is far more flammable than normal human fat.

Despite this continuing disbelief by professionals that human bodies could just plain burn, the evidence was clear... and both professional and public belief on the matter of the strange fire deaths were slowly tipping away from the ideas of spontaneous combustion and preternatural combustibility, towards the real possibility of the 'candle effect' being the most plausible answer.

By the 20th century popular interest in spontaneous combustion was waning, and professional scholars and medical men avoided the topic as, at best, a disproven idea and, at worst, a topic that could get them ridiculed and shunned among their peers.

This didn’t mean that the strange fire deaths weren’t discussed in medical journals; they most certainly were. But explanations for the deaths very studiously avoided suggestions of either an internal combustion or a preternatural combustibility, instead suggesting variations on either the 'candle effect' theory, or that the gases and wastes produced in decomposition were being accidentally set aflame by external sources. In short, it was assumed there was a mundane explanation, even if no one knew what it was; and any form of fantastic theory was flat out rejected by professional science and medical journals.

Under these circumstances, the idea of an internal combustion of the human body as both unexplained by and rejected by science appealed to authors and audiences who had a taste for strange stories. With the rise of interest in Spiritualism in the end of the 19th century, a wide range of magazines and publications had made a living presenting stories of ghosts and hauntings; and as the 20th century started, and interest in the Spiritualist movement was dying out, these same publications were looking for other unusual ideas and stories to sell... and in many of these publications, the old idea of spontaneous human combustion started to appear again.

Two important changes seem to have turned up in the reports of spontaneous human combustion around this time. First, the reluctance of the medical profession to discuss or investigate the matter of these strange fire deaths was not seen as the natural outcome of two-hundred years of study and frustration... it was instead re-interpreted as an actual conspiracy to hide the phenomena, presumably because medical professionals could not explain it and were afraid this fact would lead the public at large to question their authority. This added a sense of excitement to the reports of spontaneous human combustion, for now there was the feeling of thwarting a powerful authority by exposing the facts of a buried phenomena.

The second big change came from the idea that spontaneous human combustion, like the earlier reports of hauntings in these magazines and publications, could very well have a supernatural explanation; this would also explain why the medical professionals could not understand it, and another reason they would try to hide the phenomena. Given this thought, reports that seemed to include scientifically impossible details were favored for publication... these reports were far more interesting to the audience these publications were targeting.

All of these ideas came together best in 1932 with the publication of American author Charles Fort’s book, Wild Talents. This was the fourth book by Fort that featured a variety of strange stories mostly clipped from local and international newspapers; the different stories had been selected by Fort specifically because each seemed to present a situation that was scientifically either hard to explain or just plain impossible. In this volume, Fort presented several cases of strange fire deaths with very puzzling details, some from the early 1800’s, and some from more recent sources: cases such as that of Wilhelmina Dewar, found burned to death in 1908 on an un-burned bed... or Nora Lake, who was found burned to death in un-burned clothes in 1930... or Lillian Green, found in 1916 on a scorched floor with burned body and clothing, but no source of fire; she died in the hospital, never able to explain what happened. These details were presented with tongue-in-cheek commentary on how they were examined and dismissed by the authorities that investigated, who hoped that the cases would quietly go away.

The audience for these publications was relatively small and, with the advent of the extremely popular UFO reports that started during World War II, the reports of spontaneous human combustion lived a near forgotten existence in the back pages of these magazines. But a small audience also means very few critical observers; so the nature of the reports of spontaneous human combustion became even more mysterious over time. Author Erik Frank Russell bears the dubious honor of reporting the first case of a supposedly witnessed combustion. In the May 1942 issue of Tomorrow magazine, his article on mysterious deaths for the years 1938 and 1939 included the simple report of ‘Chelmsford woman burned to death in a dance hall.’

This one line report was a legendary time-bomb. Soon, other authors embellished the report to describe the woman bursting into flames and being reduced to ashes in the middle of the dance floor. But Russell’s simple report was based on the death of a woman named Phyllis Newcombe, whose dress had caught fire as she was leaving a dance hall in 1938; she died weeks later due to sepsis of her burns... but Russell himself apparently didn’t know this. Supporters of spontaneous human combustion were delighted with this apparent proof of the existence of the supposed supernatural phenomena, so no one at the time was interested in disproving the account.

Still, even with exciting developments like so-called 'witnessed combustions,' the whole topic of spontaneous human combustion was generally unheard of by the populace at large... until one occurrence caught the attention of national newspapers in 1951.

Mary Reeser’s death, described at the start of this article, was a picture perfect case of the new idea of spontaneous human combustion. Mrs. Reeser obliged earlier criteria for the phenomena by being an elderly woman found reduced to a pile of ashes and an unburned lower leg, and added a scientifically unexplainable detail -- her shrunken skull -- which matched the modern taste for a supernatural mystery. Even with these criteria, there seems to be two other reasons the report of her death became national news. First, she had moved to Florida from Pennsylvania only four years earlier... so the reports of her death were automatically reported in two major cities in two states, St. Petersburg in Florida and Columbia in Pennsylvania, because people both knew and remembered her well in both places; this meant the news was transmitted by the Associated Press, and was available for newspapers nation-wide to pick up.

Secondly, many figures of authority -- fire chiefs, detectives, coroners, and an anthropologist who worked with the FBI in cases of fire deaths -- were quoted as stating the case baffled them and defied their sense of what was scientifically plausible for such a death, which is an exciting thing to hear an authority figure say... since the Reeser incident, investigators of strange events have become far more tight-lipped until an official opinion has been agreed on. In the case of Mary Reeser’s death, however, the seeming admission of the authorities to the existence of a mystery they couldn’t solve was printed in newspapers across the United States (and quite a bit of Europe, too!), and instantly refreshed the public’s interest in the strange fire deaths. Magazines that had carried such stories marginally in the past trotted out their old accounts, some even giving the topic of spontaneous human combustion more room on the cover than the UFO stories that usually sold well.

Strange Associations and Interpretations

It wasn’t long before spontaneous human combustion became a prominent subject in books on bizarre phenomena. One of the earliest and most influential was Vincent Gaddis’ Mysterious Fires and Lights, published in 1967. Only one third of this volume is devoted to the topic of the strange fire deaths. Gaddis’ book is about a large variety of reported supernatural phenomena that involves unexplainable fires and lights, and spontaneous human combustion was included in an attempt to show a relationship between its unexplained fires and the other strange occurrences.

In previous centuries, beliefs about the causes of the strange fire deaths led to other fiery events being considered related to them. In the 18th century the strange fire deaths were associated with stories of people vomiting flames after drinking too much alcohol, because alcohol was believed to be the cause of the strange fire deaths. In the 19th century the strange fire deaths were associated with stories of people with burning limbs that could not be extinguished and stories of doctors igniting the gases produced by decaying corpses, because ideas of preternatural combustibility made these stories sound like they were related to the strange fire deaths. Gaddis’ book took the 20th century’s idea of the strange fire deaths as being of a supernatural origin, and associated the phenomena with other purported supernatural phenomena, cementing the public idea of the deaths as both unexplainable and paranormal.

The first full length book devoted only to the subject of spontaneous human combustion was released in 1976. Michael Harrison’s Fire From Heaven soon became the standard reference work on the phenomena as it was now interpreted, and not only added dozens of new anomalous cases, it also added a new spin on some of the original cases. For example, the case of the Countess of Goerlitz, mentioned above... whereas all the original evidence makes it clear the countess was murdered by a servant and then burned in a clumsy attempt to disguise the murder, Harrison asserted the case was an actual supernatural combustion. His argument is that the authorities of the time, faced with the unexplainable death of a prominent person, chose to frame an innocent servant rather than admit the Countess’ death was a case of spontaneous human combustion. Using logic like this, Harrison reintroduced many cases of the past to a new audience who didn’t know he was presenting his own idea of these events... and these events then became accepted by new authors as genuine, time-tested and proven cases of supernatural combustion, to be repeated without being re-checked for decades afterwards.

Harrison had many theories about the causes of the strange fire deaths. Among other things, he attempted to show a connection between spontaneous human combustion and telepathy, auras, people with unusually strong magnetic fields, geography, and ‘ritual dancing’ all to try to prove his theory of a connection between extreme emotional states and spontaneous combustion.

Though somewhat rambling and unclear, Harrison’s ideas do seem to have had one major impact: after his book, there was no limit on how bizarre the theories explaining the strange fire deaths could become. For example, theories that came after Harrison’s book included the idea that the electrical fields that exist within the human body might be capable of ‘short circuiting’ somehow, that some sort of atomic chain reaction could generate tremendous internal heat, that “geomagnetic fluctuations” cause the phenomena, or that an explosive combination of chemicals can form in the digestive system, fueled by a poor diet. This last theory was used by one author to attempt to explain why no reports of spontaneous human combustion had come from Asia... obviously, the author pointed out, the difference must be due to an Asian diet of rice and fish not promoting internal combustion. (There were a few reports from Asia, by the way... but apparently this author didn't know that!)

Many investigators made the mistake of trying to ‘explain’ spontaneous human combustion with other scientifically unproven phenomena, such as trying to relate the strange fire deaths to the locations of so-called ‘ley lines,’ theoretical lines of ‘earth force’ that run across the globe. The existence of these lines was first suggested by an amateur archaeologist named Alfred Watkins in 1921, who felt that the large number of towns and archaeological sites of interest that could be found aligned in a straight line in the English countryside must be from a time when the countryside was more heavily forested, and straight line paths with obvious landmarks would have allowed navigation through the dense trees. By 1970, however, Watkins’ ley lines were being associated with a variety of supernatural forces and assumptions of some form of ancient power flowing along actual line in the earth itself. With this in mind, Larry Arnold, in his 1995 book, Ablaze! The Mysterious Fires of Spontaneous Human Combustion, claimed that Watkins had discovered a ley line pattern in the location of a number of places called “Brent” (old English for ‘burnt’); Arnold then states that he himself drew a dozen or so ley lines on a map of England and compared the results to the locations of mysterious fires. Through this comparative method, he claimed to have identified what he called ‘fire-leynes,’ one of which is 400 miles long, and runs through five towns where (at the time) ten mysterious blazes had occurred. This same ‘fire-leyne’ was said by Arnold to have had several spontaneous human combustions along it; he cited four cases which occurred on it between 1852 and 1908.

Not surprisingly, even the mysterious and ever-popular UFOs were blamed for causing the strange fire deaths... but perhaps the oddest idea to sprout from this new sense of weirdness associated with spontaneous human combustion was the theory put forward in 1983 that the sacred image on the Shroud of Turin was probably created when the body of Jesus Christ spontaneously combusted!

Though it wasn’t as fantastic and public as all of the paranormal stories and theories flying about, all through the 20th century arguments were also being pursued for scientific explanations for the strange fire deaths. The main criteria that had marked these deaths as anomalous for two-hundred years started to yield their secrets to the scrutiny of medical and fire professionals. This increase in knowledge was largely due to one new development in the cultures of Europe... the introduction of cremation as a means of handling the dead.

The first experiments with cremation, being the total reduction of a whole body down to just ashes, started in Italy. In 1872, two separate papers had been published regarding experiments in this form of death processing; and in 1873 a Professor Brunetti from Padua displayed his furnace and the ashes it produced, as well as discussed his experiments, at the Great Exhibition in Vienna. It was at the Exhibition that surgeon Sir Henry Thompson was first introduced to the idea of cremation; and he went on to champion the idea in England with the publication of his article, “The Treatment of the Body after Death,” in the January 1874 issue of the Contemporary Review. The response to the article was encouraging enough that Thompson soon founded the Cremation Society of Great Britain, and raised enough money to build England’s first crematorium near London in the town of Woking in 1879... but red tape and public opinion prevented the crematorium from being used for human remains until 1885. Thompson had spent this down time perfecting his mechanisms and knowledge of cremation by visiting other countries and inventors, and experimenting himself using livestock carcasses. In 1885, only three cremations were performed; but by 1892, an average of 100 cremations a year were being performed.

Also by 1885, as far as the opinion of medical experts went, spontaneous combustion of the human body from an unknown internal source was simply considered a myth... yet, despite the new information the practice of cremation supplied about the conditions under which a body could be destroyed by fire, the idea of preternatural combustibility continued to be seriously considered by medical professionals as a possibility. The main reason seems to be the ongoing disbelief that a normal human body could possibly be incinerated as completely as seen in the strange fire deaths, even with the candle effect.

Another reason the theory of preternatural combustibility was still around was that, in a medico-legal sense, it didn’t pose a problem for deciding whether or not a murder had occurred. Much had been written and argued in the previous century about whether various unusual deaths involving fire had been cases of spontaneous combustion or not, precisely because if these were cases of internal combustion then no one could be found legally guilty of murder. Preternatural combustibility did not present this issue; whether or not a person displayed signs of burning better than an average person would, the legal question remained focused on the simple detail of how the fire started... so the existence or non-existence of preternatural combustibility would in no way effect a final verdict in a court case.

A further complication was that, in some ways, the new information coming from the practice of cremation seemed to support the idea of preternatural combustibility. As late as 1905 and in no less a title than the latest volume of the esteemed Principals and Practices of Medical Jurisprudence, by Dr. Fred Smith, fellow of the royal college of physicians, the possible existence of preternatural combustibility was still asserted... this was in part based on a letter from the Superintendant of the Woking Crematorium in which it was stated that the crematorium could reduce an adult human’s body to ashes in just one hour running at a temperature of 1800 degrees. This implied to many people that the strange fire deaths also had to reach these imposingly high temperatures to reduce the greater part of the victims’ bodies to ashes. However, when put into context, the problem wasn’t as difficult as it first appeared. The crematoriums were using temperatures designed to completely reduce a human body as fast as possible... and, in the strange fire deaths, the bodies were not completely reduced, only partially consumed. In many of the deaths, too, there had been a greater amount of time than one hour in which the fires could work their terrible wonders. The longer each body burned, the lower the necessary temperature for their reduction could have been.

Despite appearing to support the possibility of preternatural combustibility, Dr. Smith’s book also undercut a number of the proposed causes of this condition. In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, a number of experiments had been performed concerning the idea of alcohol making flesh more flammable... which it doesn’t. Flesh that had been soaked for a long time in alcohol burns no appreciably better than flesh that has just been doused, and neither burns very long. In every case the alcohol burns off first, and then the flame dies out trying to burn the flesh. Ironically, similar experiments had been performed in 1827, but their relevance to the argument of the strange fire deaths had never been seriously considered at the time. Dr. Smith also discusses the argument for the production of flammable gases within the body both before and after death... but, while proof definitely exists that such flammable gas can be produced, this gas, like the alcohol, burns off fast if ignited and doesn’t lead to a continuing combustion.

After all of that, Dr. Smith then mentions that fat may also have an effect on the strange fire deaths, since many of the victims were of a corpulent nature, and fat is known to continue burning once ignited; perhaps, he states, the clothes and the fat of the victims could have acted like the wick and tallow in a candle, the fat burning and the clothing being far less effected. In short, Smith proposed the 'candle effect' once again... and, though it had been ignored for nearly 180 years, it eventually proved to be a very good idea.

In the previous century, arguments had been made against the candle effect and its proposal that the strange fire deaths could be explained as the result of the victim’s clothing acting like the wick of a candle to use the victim’s own body fats to create a powerful, localized fire. It was stated by supporters of the theories of internal combustion and preternatural combustibility that the candle effect would never produce a flame hot enough to break down a body, bones included, and that it would burn slow enough that any reasonably aware person would have plenty of time to stop it. This second argument had already been challenged when it was pointed out that the victims could very well have already been dead when the fires consumed them; and now, with a better understanding of combustion and the human body, the first argument was also challenged.

In 1999, a paper was published by the Forensic Science Society in their journal, Science & Justice, with the imposing title of “Combustion of animal fat and its implications for the consumption of human bodies in fires.” The authors, John DeHaan, S.J. Campbell, and Said Nurbakhsh, had set out to burn small pigs in a variety of situations that could be encountered in fires with the hope that the results would be illustrative of the sorts of damage that could be seen by fire investigators in human bodies under the same conditions... and since the pigs were being used as replacements for human bodies, each was draped over the shoulders with a cotton/polyester blend shirt to replicate clothing that human victims would have been wearing.

What was discovered was that, once ignited, the pigs were capable of continuing to burn with no additional fuel added past their own body fats, as long as they had the charred shirt material to act as a wick. The resulting fires were quite small because of the water content of the flesh was also being boiled off, so the flames were unlikely to spread to other objects. The flames didn’t burn on their own very long, but it was undeniable that they had been self-sustaining for a short period of time. The results of these initial tests were so intriguing that John DeHaan and Said Nurbakhsh were soon funded to perform a further experiment, specifically to attempt to replicate the body damage found in many of the accounts of the strange fire deaths that had been previously blamed on internal combustion and preternatural combustibility.

The second test was carried out in 1999, and was sponsored by the BBC Television series QED, which filmed the experiment and interviewed DeHaan and Nurbakhsh for an episode devoted to the topic of spontaneous human combustion. For this test, a larger pig carcass was used that better approximated the average size and weight of a human victim, and the whole pig was wrapped in a single-layer cotton blanket to increase the area covered by a possible candle effect. The fire was initially started by a small amount of gasoline, and a carpet under the pig also added to this initial flame, but once these two fuel sources stopped burning the carcass, the body continued to burn for a further four hours on its own, using only its own fat and body tissues as the fuel... and it could have burned longer. The test was ended when it was felt no more useful information was to be gleaned from it.

In that four hour period, the fat from the pig’s body was clearly wicking up on the charred remains of the blanket; and as the burn proceeded, the bones of the thorax and limbs were exposed. It was further discovered that the nature of the flames, which kept fluctuating in temperature, was more efficient at rendering the bones brittle than a single, continuing, hot exposure. Four and a half hours into the test (three hours into the self-sustaining candle effect), the carcass burned into two pieces at the mid-thorax... and all through the burning process, the temperature in the room of the experiment stayed low enough that the experimenters were able to enter and leave as they pleased, and even filmed their interview next to the still burning body.

Some Explanations... and Continuing Controversies

This slow consumption of a body by a lower temperature flame also explains other effects associated with the strange fire deaths. The actual damage from burning is limited to just the area that the fuel source (the body) occupies, due to the minimal size of the flames and low radiant heat, and the fire extinguishes itself when the body no longer provides enough fuel. Objects just above the flames get the most heat from them, and objects and flooring under the bodies can burn due to dripping fat... and these are typically the only areas where additional burn damage is found in the strange fire deaths. Limbs are often left behind either because of a lack of good wick material clothing on them, or because they don’t contain enough body fat to continue to support burning.

The heat from these fires travels up and forms a high temperature air layer from the ceiling down that is not hot enough to cause objects to burst into flame, but is hot enough to cause plastics and waxes to melt. Previous to the 20th century, the only evidence of this layer was typically fully melted candles leaving unburned wicks behind; in modern accounts, picture frames, light switches, and other plastic items are often found melted in the rooms the fires take place in, but only above a certain height in the rooms.

In some cases where these fires occurred in rooms with poor ventilation, the fires produced a heavy smoke that contained grease from the burning body fats and soot from the clothing and body tissues. This greasy, sooty smoke coated the rooms starting from the ceiling and working its way down with the high temperature air layer. This created a yellowish orange greasy film that covered the walls, windows, and ceiling of the upper part of the room... an effect that was described in the death of the Countess Cornelia di Bandi in 1741. Thus a large number of cases attributed to internal combustion and preternatural combustibility are absolutely explainable by the candle effect, now re-named as the 'Wick Effect' by DeHaan and associates.

Even before the QED episode on spontaneous human combustion aired, through the decades of the 80s and 90s, newspapers, television, and popular magazines in England and the United States had slowly shifted from presenting the topic of the strange fire deaths as a serious subject, to more of a joke. The QED episode cemented this developing public idea.

But supporters of the theories of internal combustion and preternatural combustibility had a different view of the evidence produced by DeHaan and Nurbakhsh’s experiments. The circumstances and the results, it has been pointed out, don’t entirely match many of the combustions it is assumed the experiments explain. The pig carcass used was cleaned, so it only presented muscle, fat, and bone for fuel... not the internal organs, which would presumably make the torso harder to burn through. Using gas to start the fire didn’t duplicate the proposed causes of the fires -- being candles and cigarettes -- because gas burns more readily and hotter. Most of the reported cases happened on uncarpeted floors, so using a carpet to add to the burning was a cheat. Also, most of the cases were found on floors that had just charring or less damage... the pig in the experiment burned through the floor it was on, and still wasn’t as incinerated as most cases of the strange fire deaths. Finally, the experiment took too long to match cases reported in which victims only had one to two hours to have most of their bodies reduced and, even with over six hours to work with, the pig carcass was not as burned as the bodies reported in the strange fire deaths. So the believers have not been convinced.

All of which brings us to the current state of affairs where the concept of spontaneous human combustion exists. On one extreme are the believers in the supernatural (or at least unexplained) nature of the phenomena; the pre-existing belief in a conspiracy to cover-up the topic of spontaneous human combustion means that any evidence presented to them that tends to disprove the existence of the phenomena is simply ignored on the suspicion of being a calculated lie. On the other extreme are the believers in the absolutely scientific nature of the phenomena, who feel their arguments have been proved and that any strange event that doesn’t fit the scientific explanations is either mere folklore or a flat-out lie designed to garner public attention. Both groups feel that the history of the strange fire deaths supports them... and both groups are right, depending on what parts of history they pick and how they view it.

A case in point: Mary Reeser’s skull.

As mentioned at the start of this study, reports regarding the death of Mary Reeser listed her remains as ashes, one leg (intact from the knee down), some fused vertebrae, and her shrunken skull, reduced to the size of a teacup. But heads don’t shrink when exposed to heat, they expand... and, in extreme temperatures, they explode. So Mary Reeser’s anomalously shrunken skull has been pointed out for years as proof of the supernatural nature of the death that overcame Mrs. Reeser. Not surprisingly, believers in the non-supernatural nature of Reeser’s death have a scientifically acceptable explanation for the shrunken skull; simply put, it’s not a skull. It’s a knot of muscle from the back of Reeser’s neck that has charred into a hard ball that was mistaken for a skull.

So here’s the trick: both theories have evidence for and against them. Evidence for the supernatural shrinking of the skull are the statements of coroner Ed Silk, who handled the object and called it a shrunken skull; the evidence against the theory is that it presents what appears to be a scientific impossibility. Evidence for the mistaken knot of muscle theory is that it is scientifically plausible; and the evidence against this theory is that the idea is not actually based on direct evidence... it is an educated guess at what sort of remains could be found that might be mistaken for a skull.

The skull and/or knot of muscle -- whichever it might have been -- was likely buried along with Mrs. Reeser’s foot. The object was never tested further, nor was it sent to the FBI to be examined. So the question of whether or not Mary Reeser’s shrunken skull was actually found tends to be decided not by evidence, but by preference... those who believe in supernatural human combustions see evidence for a shrunken skull; those who believe in a rational scientific form of burning see evidence for a mistaken object.

About the only thing the two groups agree on is that the strange fire deaths have happened, and likely will continue to occur. How these deaths are viewed and treated by the public and news agencies will always depend largely on the current public idea of both the causes and meanings of these events... but to those who are left behind by a loved one who suffers this fate, the loss will always be painful, and likely complicated by the reactions of the curious.