Kraken: Myths, Legends, and History

The Kraken, the great beast of the seas, is a popular creature modernly seen often in comic books, games, television shows, and movies... and from these sources is quickly gathered the general idea of the beast as a gigantic squid that attacks ships, and is powerful enough to sink them if it so desires. This is how the creature was portrayed by Jules Verne in his book 20,000 Leagues Beneath the Sea, as well as in Disney's movie version of the story; and again the beast was portrayed as such in Disney's more recent Pirates of the Carribbean movies.

Of course, scientists are quick to point out that while the legends of the kraken are likely based on true sightings of giant squids, the squids in question were never large enough to sink a ship, nor likely to want to do so... the tremendous size and aggressiveness of the legendary kraken is pure exageration and fantasy attached to a relatively rare, but very real, aquatic wonder.

And the funniest part of all of this is how mistaken both ideas are.

The kraken, as originally reported over three hundred years ago, was not described as a squid, nor was it likely to have been based on one; and it was never accused of being aggressive. What's more, the trail from the first reports of the kraken in scientific literature of the mid-1700's up to the modern concept of the creature as a violent giant squid demonstrates exactly how little facts matter compared to convenient assumptions.

The Original Kraken

The kraken first came to the attention of the world in 1751 due to the publication of the Natural History of Norway, written by Erik Pontoppidan [1698-1764 CE], bishop of Bergen, who collected stories of the beast from the fishermen who claimed to encounter it. Also called the kraxen or krabben, the creature never fully came into view due to its immense size and its mostly underwater existence... but the details that Pontoppidan collected did lead him to beleive that similar creatures had been unknowingly reported by other authors many times in the past. Though Pontoppidan was unable to specify the actual size and appearance of the kraken, he still felt that the information he had gathered was enough to entice future investigators to discover more about the animal.

During hot summer days the kraken often rose to the surface of the seas near Norway; it never came to the surface during rough seas or weather. The beast was usually encountered anywhere offshore that was at least a depth of 80 fathoms. If a depth check by fishermen came back as less than thirty, it was assumed a kraken was under the boat. Krakens attracted fish; there were always big schools of fish – especially cod or ling – in the water above the submerged beast. So if a kraken was located, sometimes up to 20 boats would gather above it to catch the plentiful fish.

If the depth of the kraken showed that it was rising to the surface, the fishermen had to row away until they detected a normal depth for the area. Soon after, the back of the creature would rise to the surface, looking like a number of small islands surrounded by sea-weed, with stranded fish flopping about until they reached water again. Next, a number of “horns” rose up, as tall as the masts of middle-sized ships, thicker at the base than the top. Pontoppidan felt these were the arms of the creature, used to move it around. He stated the visible area of the creature’s back was estimated to be a mile and a half in circumference, but also stated that he chose to present the smallest estimation the fishermen gave him, “for greater certainty.” After a short time, the kraken slowly re-submerged, creating swells, eddies, and a whirlpool that sucked everything too close down with it.

The kraken spent several months eating, followed by several months excreting. This excretion colored and thickened the water, but was highly attractive to fish. Great schools of them gathered above the kraken to eat this waste… and then were eaten by the kraken.

Pontoppidan stated that the kraken could probably grab a boat and drag it under if it chose to; however, it was never actually known to be aggressive. All human deaths and injuries it caused were accidental, and generally due to fishermen not reacting fast enough to the kraken’s presence. The bishop tells that “a few years ago near Fridrichstad,” a small boat with two fishermen came too near a rising kraken, and could not get away in time. One of the creature’s ‘horns’ crushed the front of the boat, and the fishermen clung to their floating wreck until they got back to shore.

Pontoppidan also relates an account from the Reverend Friis, Minister of Nordland. In 1680 CE, what was assumed to be a young kraken swam into the waters between the rocks and the cliffs in the parish of Alstahaug. In moving about, it tangled itself up in the rocks and caught its ‘horns’ among trees near the water; unable to escape, the beast eventually died. Its body took a long time to rot away, and the stench made the area intolerable... unfortunately, no one took measurements or drew a picture of the body.

And so concludes Pontoppidan’s report on the kraken, to which he added his beliefs that the beast is a form of polype or starfish, and that it is possibly responsible for reports of vanishing islands worldwide.

Kraken Confusions

Over the next fifty years, the popular idea of what the kraken was altered due to confusion with other legendary beasts, and difficulty in locating Pontoppidan’s book. The kraken tale was mixed up with previous stories of living islands and with tales of sea-serpents of any description; any such report was treated as evidence of the kraken.

For example, a well-known tale of an Arabic sailor named Sinbad told how he was one of several sailors who disembarked on a strange flat green island in the middle of the ocean to stretch his legs... and was the only person to survive when the 'island' sank beneath the waves and swam away. Another well-known tale told of Saint Brendan of Ireland being on a boat that moored at a hilley little island for a night; when, in the morning, the sailors built a fire to cook a meal, the island shuddered and began to sink and swim away. There was no loss of life, and much to everyone's surprise Brendan had known it was a fish the whole time... God had told him it would be safe for their ship to moor on it for the night (Brendan chose to sleep on the ship, by the way). From these tales of the 'island fish,' came new stories that told how sailors had landed and set up camp on a kraken, only realizing their error when they started a campfire... usually with a great loss of life in the whirlpool created as the kraken sank beneath the waves.

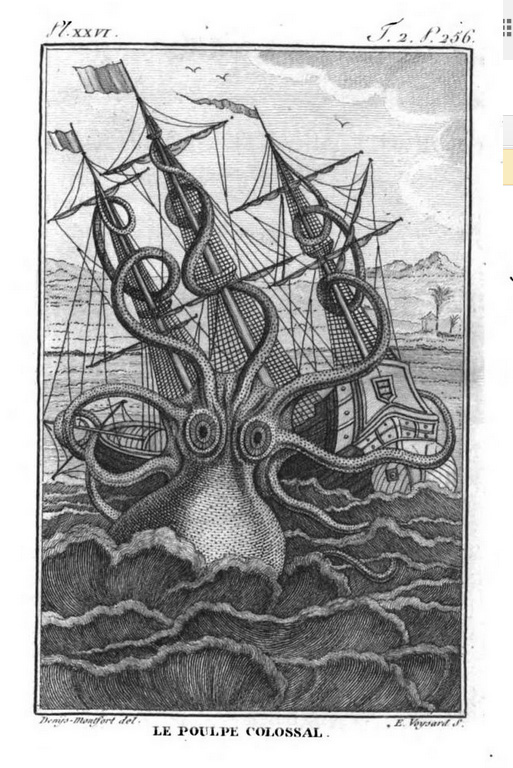

In 1801, a Frenchman named Pierre Denys de Montfort [1766–1820 CE] published Histoire naturelle, générale et particuliere des Mollusques, a book meant in part to prove the existence of giant octopuses; and to help his book sell, he claimed that the kraken was actually a type of giant octopus. He stated that the reported “horns” were tentacles, and the fish-attracting excrement was octopus ink. He also included an illustration of a giant octopus pulling a boat under the water, and claimed that Pontoppidan stated that krakens did this (which he didn't state and they don’t do).

Montfort's Octopus [Larger version here]

Montfort's Octopus [Larger version here]

Montfort’s book was laughed at by serious minded people; but by 1819 naturalists and scientists began to find decent evidence for the existence of the giant squid, and started to believe Denys de Montfort’s claims regarding the kraken... except they suspected it was a squid instead of an octopus.

This new scientific opinion of the matter was assisted by the rarity of Pontoppidan's book. By 1860 Pontoppidan's original book had become so hard to find that what people knew about his claims for the kraken came from other people's accounts... and these were often wrong. Among other strange ideas, it was claimed that Pontoppidan had stated the kraken was so large when surfaced "that a whole regiment of soldiers might with ease maneuver on the back of the floating monster," which was big enough a fish story that no one believed it. But, simply put, Pontoppidan never said this; unfortunately, no one seems to have known that. This false claim of the kraken's size, among other false claims attributed to Pontoppidan after the fact, were then and are still generally pointed to when supporters of the idea of the kraken as a giant squid need to discredit any details from Pontoppidan's original report.

One more publication assisted the public misconception of the kraken as being a giant squid, though inadvertently. Published in 1870, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, by well-known author of the fantastic Jules Verne [1828-1905 CE], proved to be an enormously popular book. In this story of a sub-marine adventure, Verne makes many mentions of the kraken and Pontoppidan, and also has a scene in which the lead ship is attacked by a giant squid... which, combined with the then stated opinion of many learned men about the kraken and the giant squid being the same creature to start with, largely cemented the new public idea of this being correct.

Despite all of the smoke and mirrors to make the “kraken is a giant squid” argument work, in the end there is one main difficulty: Pontoppidan knew the difference between a squid and a kraken -- he described species of both, along with starfish, in the same chapter of his book -- so Pontoppidan was not confused about what he was reporting. He had not seen the beast, but from the descriptions he gathered the bishop was very clear that he felt the kraken was, in fact, a gigantic starfish; and, if it ever existed to start with, perhaps it is still in the oceans near Norway waiting to be truly re-discovered.

Anomalies -- the Strange & Unexplained, as well as my other website -- Monsters Here & There -- are supported by patrons, people like you! All new Anomalies articles are now posted for my patrons only, along with exclusive content made just for them. You can become a patron for just $1 a month!

|