1930, November: Lake Anjikuni Disappearances

The Legend:

In November, 1930, a man named Joe Labelle walked into an Inuit village near the shore of Lake Anjikuni (or Angikuni), in the Kivalliq Region, Nunavut, Canada, and found himself perplexed. Lake Anjikuni is about 500 miles north of the village of Churchchill, and Labelle, a fur trader, had visited the village many times before over the years... but this time he found it unnaturally quiet, and for good reason. Not a single person was to be found in the village, nor any animals -- pets or wild.

According to the report that Labelle left with the Northwest Mounted Police, he had gone a few miles out of his way that day to visit friends in the village. Labelle had initially yelled a greeting from the edge of the village and gotten no reply, a situation that was already strange. He started to check the huts and found each empty, but in a strange way... some had pots of food still hanging above long cold fires; in one hut he found some sealskin clothing for a child that was being mended, the needle and thread still in it as if simply set aside. Rifles had been left behind in the huts, still standing by the doors. On the shore of the lake were three kayaks, including the village headman's; they had been abandoned so long ago, that the action of the lake waves had torn them up in their owners' absense.

Stranger still were the two discoveries made outside the village. On one side, and about 100 yards from the village, seven dead dogs were discovered, tied to some tree stumps. On the side of the village opposite the dogs, a stone cairn grave had been opened and the stones re-stacked into two piles... the body they had covered was gone.

Later examination by experts called in by the mounties determined that the dogs had starved to death, and that the village had probably been deserted two months previous to Labelle's discovery, towards the start of Winter, a conclusion that was based on the type of berries found in the cooking pots. Simply put, the evidence seemed to say that the thirty inhabitants of the village had simply abandoned their homes at a moment's notice and never came back. Where they went and why has never been determined.

Origins of the Legend

The legend of the Lake Angikuni disappearances, as given above, comes directly from Frank Edwards' 1959 book, Stranger Than Science. This is because Edwards' version of the story - including the misspelling of the lake's name as Anjikuni - is what almost every author after him has either repeated, or expanded on. Popular versions now tend to include accounts of lights in the sky and other phenomena to imply the event had something to do with UFOs, which are new inventions.

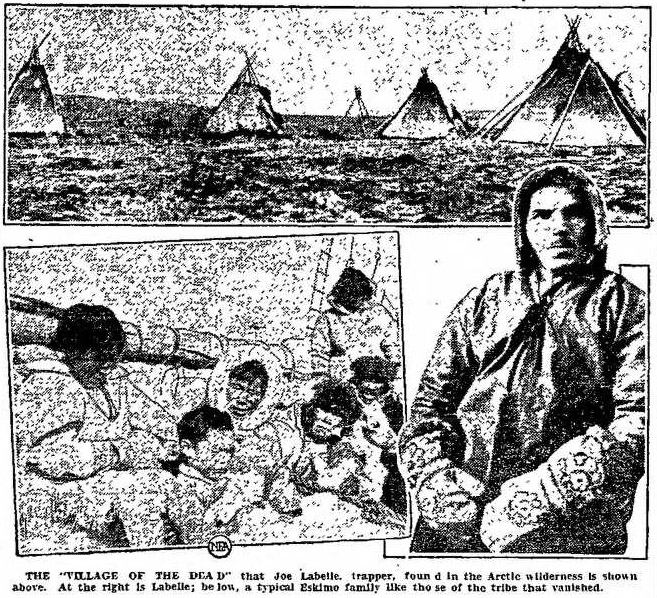

But Frank Edwards was not the first to write about the village. I suspect he got his story from FATE Magazine, though I have not been able to track down said possible source yet; but what I have found is a copy of a news report that was transmitted to papers by the NEA (Newspaper Enterprise Association) on November 26, 1930. The article, written by Emmett E. Kelleher, was entitled "Vanished Eskimo Tribe Gives North Mystery Stranger Than Fiction," and was accompanied by the photos displayed above of the village, trapper Joe Labelle, and "a typical Eskimo family" like those that vanished.

The story, as Kelleher states it, started when Joe Labelle arrived by canoe at the village. He beached the canoe about a hundred yards from the village and approached it shouting out greetings... but instead of a reply, all he met with were two "husky" dogs that were half-starved and that crawled towards him, "whining dolefully." The bodies of an additional seven dogs were just laying around.

There were only six tents in the village, and Labelle began to investigate them. The article quotes Labelle: "I'll admit that when I went in the first tent I was a little jumpy. Just looking around, I could see the place hadn't known any human life for months, and I expected to find corpses inside. But there was nothing there but the personal belongings of a family. A couple of deer parkas (skin coats) were in one corner. Fish and deer bones were scattered about. There were a few pairs of boots, and an iron pot, greasy and black. Under one of the parkas I found a rifle. It had been there so long it was all rusty." In short, everything looked as if it had been left that way by people who fully expected to come back... but had not.

Labelle found all the other tents in a similar state, and was followed the whole time by the skeleton-thin dogs. He estimated that no one had been in the village for at least twelve months, and that 25 men, women, and children in total had vanished. Spooked by the situation and wondering if the old Inuit legends about an evil spirit named Tornrark had any truth in them, Labelle wandered down to the nearby lake shore. This is when he discovered the open grave. The cairn of stones had been removed from the grave and piled on one side; the cairn itself was empty. He had no way of estimating how long ago it had been done.

Labelle spent a few more hours in the village. He caught some fish in the lake, and gave these to the dogs, but left well before he might have to spend the night there. He could see no obvious reason why the Inuit would have left their lives behind. Over the rest of the season, Labelle asked about the residents of the village at each Inuit habitation he stopped at. No one knew what had happened but, in general, they all blamed the evil spirit Tornrark for the event.

The Northwest Mounted Police had no better luck investigating the village and interviewing people... though some odd things were discovered that might have been related. In an Inuit village 150 miles north of the Lake Angikuni village, a ten-year Inuit boy that was not part of any of the local tribes had wandered in a few months earlier and been adopted by the group. But neither the boy nor the group were talking about this event beyond that, so his true origins remained a mystery.

Another strange matter was that of an Inuit named Saumek, who was brought to a hospital on the Hudson Bay railway for treatment of frozen legs. Since he might know something about the village disappearance, a translator was found so he could be questioned; but it didn't amount to much. Saumek mentioned Tornrark and refused to answer questions. The police then took the questionable approach of trying to get Saumek drunk to see if it would loosen his tongue... but the Inuit refused the drink offered by the translator, because he didn't like the taste of whisky.

At the end of the newspaper article, Kelleher assures us that the police were still investigating. Thus ends the earliest version of the story of the Lake Angikuni disappearances I've found.

End of the Legend?

Since the publication of Frank Edwards' book, there has been many attempts to debunk the original story, and I'm still tracking down these sources. The earliest after Edwards' appears to be an article in FATE Magazine of November 1976 (one of the few not in my collection, dang it!) by Dwight Whalen, called "Vanished Village Revisited," which is said to have characterized the article as mainly the result of the author, Kelleher's, fertile imagination.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police has dismissed the story as an urban legend on their website, stating that their records show nothing of the sort ever happening. It does need to be noted, however, that their short statement also makes it clear that the RCMP considers Frank Edwards' book to be the first printing of the story; whoever wrote the statement was unaware of the earlier newspaper accounts in 1930. I mention this mainly because it may have led to the next notable debunking of the tale, John Robert Colombo's Mysterious Canada, published in 1988. Again, I need to track down a copy before I can really assess the evidence that Colombo claims to have... and I do need to assess it, for the simple reason that he claims to have seen a report from the RCMP that the RMCP themselves appear to be unaware of!

Colombo is credited with claiming to have seen a RCMP report by one Sergeant J. Nelson issued on January 17, 1931, less than two months after the original newspaper reports. Nelson is said to have concluded the story was untrue because his interviews couldn't turn up any trappers or Inuit that could confirm the story, and that Joe Labelle was new to the North and worked far away from Lake Angikuni... so was very unlikely to just drop by there. Colombo is then said to add that the author of the original account, Kelleher, was known for writing imaginative stories, and that the photo of the village presented with his account was actually taken in Churchill in 1909 by an RCMP officer that had allowed Kelleher to borrow the photo.

No matter what the sources above say about the matter, I find I suspect the original story by Kelleher for one simple reason... if two dogs are starving, yet there are seven dead dogs nearby, then why exactly are the two dogs starving?

Anomalies -- the Strange & Unexplained, as well as my other website -- Monsters Here & There -- are supported by patrons, people like you! All new Anomalies articles are now posted for my patrons only, along with exclusive content made just for them. You can become a patron for just $1 a month!

|