1891, February: James Bartley, the ’Modern Jonah’

In June and July 1891, American newspapers were abuzz with the story of a singular event that happened in February of that year; the earliest I've found the story in newspapers is June 28, 1891, after the sailing vessel Star of the East docked on June 23 at New London, Connecticut, in the United States, having completed a two-and-a-half year trip. A statement of a remarkable nature was presented by a thirty-eight year old sailor aboard the ship by the name of James Bartley, which was vouched for by the captain and crew.

In February 1891, the Star of the East was near the Falkland Islands off South America, when the lookout sighted a large whale. Two longboats were dropped and the hunt was on. Two harpoons, one from each longboat, were sunk into the whale, which fought hard. The whale dived and the harpooners started to pull the slack line back into their boats, when the whale re-surfaced and started to beat wildly with its tail. One of the longboats managed to get away, but the other was struck by the animal's nose and tipped over... and by the time the second longboat could perform a rescue, one man had drowned and one was missing and presumed drowned.

Within a few hours the dead whale was pulled alongside the Star of the East, and the crew was busy cutting it up and retrieving the fat. The job took up the rest of the day, and a good part of the night, and then work resumed about noon the next day. It was on the second day that something strange was discovered; as the stomach was freed and brought to the deck for rendering, it was seen that something bunched up within it was showing spasmodic signs of life. When the stomach was cut open, they discovered the missing sailor -- James Bartley -- curled up and still alive, though just barely, thirty-six hours after he went missing!

He was laid out on the deck and splashed with sea water; the whale's gastric juices had bleached Bartley's face and hands to a deathly white and wrinkled them. For two weeks he was kept in the captain's cabin; physically, he recovered fine... but mentally he was unstable. But by the third week Bartley had fully recovered, and resumed his duties.

After he had recovered his senses, Bartley told how he remembered being thrown from the boat and into the water, where he was engulfed by darkness and felt himself slipping along a smooth passage that seemed to move and carry him forward. He came to an area with more room in it, and was able to reach around. Upon feeling a yielding, slimy substance as the walls, he realized he had been swallowed. There was plenty of air, but it was terribly hot in the stomach and this drained his energy; that and the horror of his eventual fate caused him to lose his mind and pass out. After that, the next thing he was reasonably sure of was waking up in the captain's cabin.

The Implications

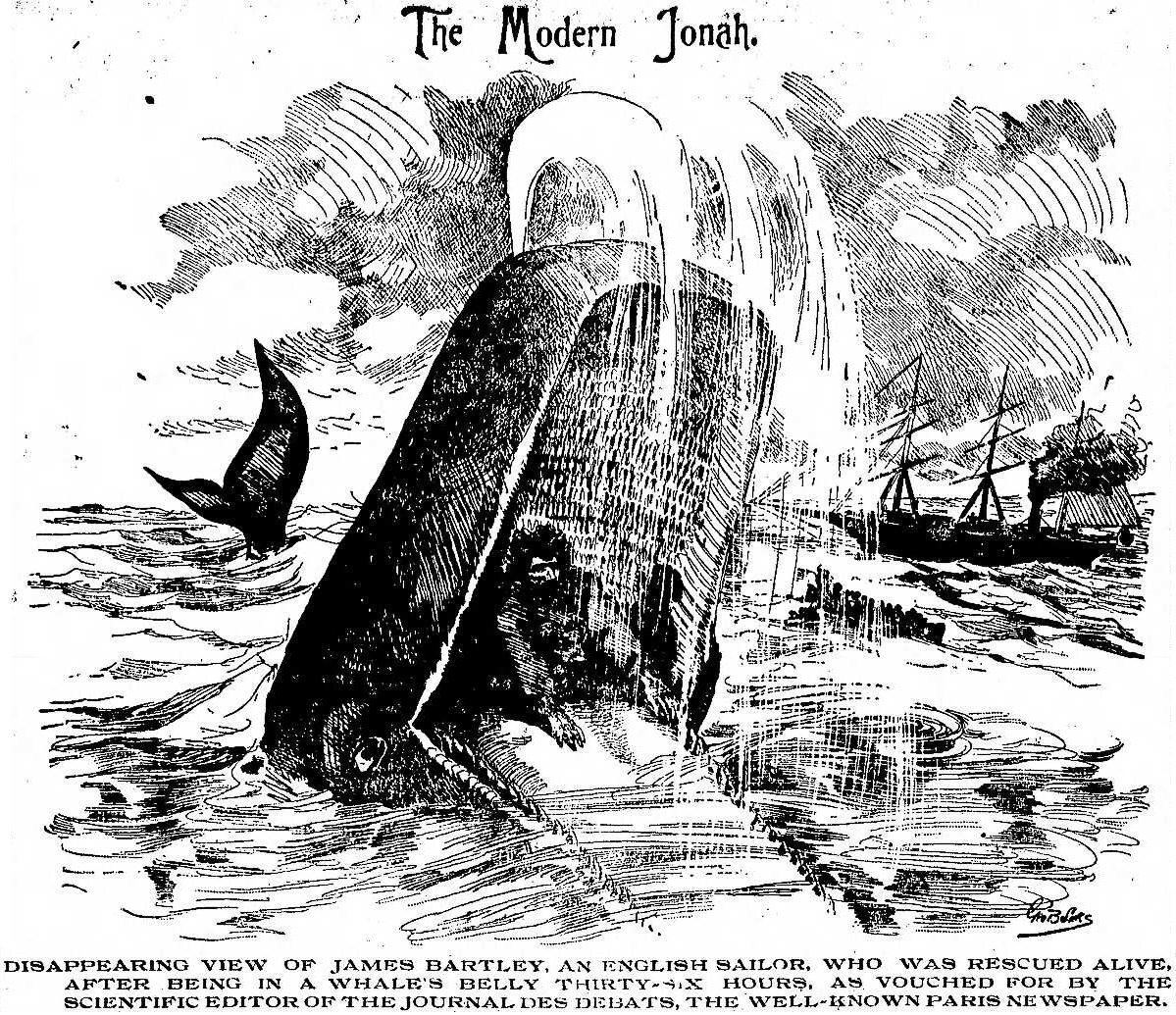

Illustration from an 1896 newspaper [Larger version here]

Right from the start, newspapers dubbed James Bartley "a modern Jonah," in direct reference to the story in the Holy Bible of the prophet Jonah who was swallowed by a great sea creature and then expelled alive three days later... and, not surprisingly, religious groups soon grabbed onto Bartley's story as proof that the Biblical story of Jonah had a basis in fact.

The timing was perfect from the point of view of these religious groups. Scientifically minded people had been ridiculing many stories in the Bible as being sheer fantasy since, scientifically, they didn't make sense; and this always came with the implied idea that these stories were therefore a form of nonsense. In short, scientific authorities were competing with religious groups for people's beliefs. Bartley's story changed that dynamic.

The veracity of Bartley's story was soon being defended by marine scientists from France and England explaining that whales had been found with squids larger than a man in their stomachs (ignoring that squids had no bones and so, of course, were relatively easy to swallow in comparison). In addition, within a year of the first report, newspapers that repeated Bartley's story now tended to also assert that several unnamed whaling ship captains had stated that men were often swallowed by whales, and that Bartley just happened to be the only one known to survive.

So Bartley's experience was essentially taken as proof that the Biblical story of Jonah being swallowed by a great creature and living to tell the tale -- which was one of the most scientifically ridiculed stories in the Bible -- was, in fact, scientifically possible. The Bartley story became so well known that it actually changed the text of the Bible itself; previous to 1891 most English versions of the Bible tell of Jonah being swallowed by a 'great fish'; it's only after 1891 that most English versions of the Bible tell of Jonah being swallowed by a whale.

For fully sixteen years, Bartley's story was considered proof of the Biblical tale of Jonah, and was quoted not just in newspapers and magazines, but also in scholarly studies of the Jonah story in encyclopedias and journals. Then, in 1907, some new information came out in The Expository Times, which was a journal established in 1889 for the scholarly study of the Bible. A gentleman named A. Lukyn Williams had made some basic inquiries with the hope of getting a statement from the captain of the Star of the East concerning the Bartley incident. He found that the Star of the East was a British ship that had sailed from Auckland, New Zealand, on December 27, 1890, and had docked in New York on April 17th, 1891 -- not at New London, Connecticut, nor on June 23 -- and that it had been commanded by a Captain Killam. On November 27, 1906, the captain's wife wrote to Williams... from Yarmouth, in Nova Scotia, Canada:

"My husband asked me to write. There is not one word of truth in the whole whale story. I was with my husband all the years he was in the Star of the East. There was never a man lost overboard while my husband was in her. The sailor has told a great sea-yarn. I wish, if it is not too much trouble, to send us one of the papers with the yarn in."

This statement was naturally taken as damning evidence, and skeptics gleefully jumped on it while believers quietly divorced themselves from Bartley's story... but no one asked two very important questions: Why didn't Captain Killam make this statement at the time of the original reports, when newspapers were claiming he supported Bartley's story? And, secondly, if Killam originally supported the story, why had he changed his mind? One possible answer to both questions is that the story may have only been told where and when Captain Killam would not have heard it, and that he had set back out to sea before he could refute it. The earliest published article about Bartley's story shows that this last thought might be right.

The first mention of the Bartley story in a newspaper came in the June 28, 1891, edition of the St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat of St. Louis, Missouri... which is a town 950 miles away from New York City, New York. The earliest I've found the tale appearing in a newspaper in New York itself is on July 5, 1891, in The Sun of New York City, New York: and this newspaper states it got the story from the St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat! So the story did not first appear in either Connecticut nor New York; and, given that the Star of the East had actually landed at port in New York back in April of the year, it's very likely that Captain Killam and the ship had already left for their next voyage before the story had a chance of reaching them.

The Return of the Legend

Not surprisingly, interest in the Bartley tale seems to have died down after the denial issued by the wife of the Star of the East's captain... but that wasn't the end of the matter. Many religious groups still repeated the tale in their small magazines, continuing to see it as a useful way of confirming the possibility of the Jonah story in the Bible to their followers. It was from one of these publications that James Bartley's questionable story of survival was to once again rise to fame.

On December 27, 1927, the tale of James Bartley's survival was featured in an extremely well-known syndicated cartoon strip. And, while this may sound like a minor event, this simple publication once again revived the whole story in popular culture as an accepted, though strange, fact. This is because the syndicated cartoon strip the story was featured in was called Ripley's Believe It or Not!

Created by Robert Ripley in 1918, the Believe It or Not! strip soon grew to amazing fame as Ripley daily presented a seemingly endless list of bizarre, but supposedly true, events and facts in a simplified cartoon fashion. Ripley grew to have a reputation of only printing stories he could prove true, often defending himself successfully against doubters, until it became a simply accepted idea that any story he printed was true, no matter how outlandish it might seem.

This wasn't a correct assumption, however. In many cases Ripley didn't defend the truth of a story he printed, but rather said he was presenting the story as his source for it presented it... leaving the possibility that his source might be incorrect, but that wasn't Ripley's fault. In the case of the Bartley story, Ripley's source was one of those small religious magazines that had repeated the tale as confirmation of the possibility of the Jonah tale in the Bible. So Ripley had not double-checked the story... yet his presentation of it in his regular syndicated strip was essentially proof to the public at large in the United States and Canada that the tale of James Bartley's survival was, theoretically, a statement of fact.

As such, Bartley's tale once again began popping up in newspapers and magazines as a strange 'fact'... but what tended to be mentioned was just the minor details that had been featured in Ripley's cartoon, stripping the legend down to a very basic story: that in February 1891, James Bartley, swallowed by whale, survived after many hours in its stomach. For the most part, the statement of Captain Killam's wife was now completely forgotten, as evidenced by the new attempts of skeptics to insist on either the impossibility of a whale being able to swallow a human, or the impossibility of a human surviving such a fate; and there was a definite disagreement among skeptics on the question of whether or not a whale could swallow a man.

In April 1947, a magazine called Natural History printed a letter that they had received from a reader that summed up an account of the James Bartley story the reader had run across; the magazine was asked if the story was true. The magazine's response was to have an expert on whaling and whales, a Dr. Murphy, respond to the letter in the same issue. The response was very succinct: the story was false, and mostly because it would be impossible for a man to survive within a whale's airless stomach any longer than they would if held under water. Surprisingly, the expert admitted that men had probably been swallowed by whales from time to time, but none had ever been recovered, and they would certainly never be found alive.

This simple exchange led to wonderful fruit, for two months later in the June issue of Natural History another letter was printed... and it told a remarkable tale.

The One that DIDN'T Get Away

This second letter was written by a Dr. Egerton Y. Davis, Jr., from Boston, Massachusetts, who wished to tell of his experience as a young surgeon on the ship Toulinguet in February or March of 1893 or 1894. He was working with the sealing fleet out of St. Johns, Newfoundland, when a young sailor out hunting had the unfortunate luck to become separated from the other hunters on the ice and to fall into the ocean... and, in full view of his comrades, an out-of-place sperm whale swallowed the poor man. One of the small sealboats managed to hit the whale with its cannon, and the wounded creature headed out to sea. The whale was found floating belly-up by one of the longboats searching for seals on the following day. It was impossible for the small crew to bring the whale to the main ship, but through an extraordinary effort they managed to cut open the whale and remove it's gas-filled upper stomach; this they brought to the young Dr. Davis in the hopes of recovering the young man's body to return to his home.

Dr. Davis quickly found that his scalpel had no effect on the tough stomach, and had to trade up to a sharp galley knife (which I really hope didn't then go back to the galley!). Once opened, the stomach expelled an "overpowering stench;" the man's body was partially digested where the skin was exposed, and covered with a layer of snail-like mucus. The man's chest had been horribly crushed, so he was likely well dead before he reached the whale's stomach. Strangely, some lice on the man's head still showed signs of life despite the circumstances. Given the horrific appearance and smell of the body, it was quickly decided that a burial at sea was a far better choice than sending him home to friends and family.

And so ends the amazing tale told by Dr. Davis.

The next edition of the Natural History magazine didn't come out until September, two months after they published Davis' letter; and by then, lots of letters had been received regarding Dr. Davis' statement. The most interesting one was from a Yorrick M'Connachie of Chicago, Illinois. According to Mr. M'Connachie, he had an uncle who had served as a seaman on the Toulinguet that had often told the story of his unfortunate shipmate's fate. The uncle had apparently claimed to have been on the longboat that cut up the whale, and also claimed to have been the only man to stay with Dr. Davis during the long examination of the body... which was an amazing corroboration of the doctor's story!

But there was soon further developments in regards to the story... and not good ones. First, it was noticed by the staff at Natural History that the "modest check" sent to Dr. Davis in thanks for his letter and story had remained uncashed. Attempts to contact him elicited no responses. Then a letter was received from a woman named Mrs. May C. Sax that pointed out some unfortunate information: Dr. Davis' letter had reminded her of the famous physician Dr. William Osler. Why? Because Dr. William Osler loved to play practical jokes; and because when he did so, he liked to use a different name... and that name was Egerton Y. Davis!

As if this detail wasn't bad enough, Mrs. Sax also added two more little details: first, that Sir James M. Barrie had also used an assumed name when playing practical jokes... the name "M'Connachie." And, secondly, that the "Y" in the name Egerton Y. Davis, stood for the name "Yorrick," the name of the jester from William Shakespeare's play Hamlet. So not only was Dr. Davis' letter likely a fake, so too was the second letter from "Yorrick M'Connachie"!

Finally, before the September issue of Natural History had gone to press, the staff heard back on the check they had sent to Dr. Davis. The magazine received a letter from the director of "one of the country's foremost hospitals" which was nowhere near Boston, which Dr. Davis had given as his address. The check had been endorsed, but not cashed... and since no one in the hospital could locate a Dr. Egerton Y. Davis Jr. anywhere, they chose to mail the check back to Natural History magazine. So Dr. Davis had vanished as completely as the credibility of his story, which Natural History officially set to rest in the letters section of their September 1947 issue. And so ended the only other claim of a man being swallowed by a whale that I know of.

None of this drama had any effect on the popularity of James Bartley's tale, however, which was now associated with a newly rising interest in not just strange stories, but paranormal stories as well. Bartley's account started to appear in longer versions once again in various magazines devoted to stories of ghosts, UFOs, and psychic powers. It was from this strange venue that the legend was to be re-sculpted one last time into its modern version.

The Continuing Growth of the Legend

The last re-working of the legend came in 1959 from popular radio personality and author, Frank Edwards. In his book Stranger Than Science, in a short section titled "A Modern Jonah," Edwards recounted Bartley's tale once again, but with some notably new details. This was not an odd practice for Edwards, and most of the supposedly 'true' stories in his volume were enhanced with new -- but fictional -- details to make the stories more exciting and appealing. Unfortunately, the sheer popularity of this book pretty much cemented Edwards' new details into the common public version of Bartley's legendary encounter with the whale. In brief, the Edwards version of the legend runs thus:

In February 1891, the Star of the East was sailing a few hundred miles east of the Falkland Islands off South America, when the lookout sighted a large sperm whale and the longboats were sent out. the whale was harpooned, one of the boats was capsized, and the two men were lost, both presumed drowned.

The work started on the whale's carcass, and it was around eleven that night that the sailors noticed the stomach was moving. The ship's doctor was called to find an explanation; having none, he cut the stomach open. Inside was found James Bartley, one of the two missing men, curled up and unconscious, but alive!

He had been in the whale's stomach for fifteen hours, and it showed; all the hair on his body was gone, his skin was bleached white, and he was nearly blind. Although he was quickly revived, it was a month before he was both healthy and rational enough to make sense of his experience. He remembered being flung in the air, and seeing the whale's huge mouth come towards him when he hit the water; he felt stabbing pains as he dragged across the mammal's tiny teeth, and then he slid down a slimy tube to where warmth and a lack of air knocked him unconscious... then nothing, until he came to his senses a month later.

It had been Bartley's first day as a sailor, and, understandably, his last. He spent the remaining eighteen years of his life working as a cobbler in his native Gloucester; when he was buried, his tombstone featured a brief account of his adventure and a footnote: "James Bartley -- 1870-1909 ... A modern Jonah."

I will also add that Edwards further stated that the unnamed doctor aboard the Star of the East wrote a record of the event at the time it happened, which was signed by all members of the ship's crew. This would certainly be worth finding... if it existed, which I see no reason to expect. Oh, and James Bartley's home town was identified in the July 1891 newspaper account of the incident as New Bedford, not Gloucester.

Although a few other prominent authors have altered the details of the legend, none have had the same effect on the popular idea of Bartley's story as Edwards has enjoyed. This is because no other author on strange topics ever had the sheer public exposure that Frank Edwards had. He presented stories such as Bartley's on a weekly radio program; and when he published collections of the stories he told, the books fairly flew off the shelves and went into multiple printings in the first few years. As a matter of fact, I personally have a copy of Stranger Than Science published in Japanese that I bought while visiting Japan in the year 2000... so Edwards' version of Bartley's tale has definitely been seen worldwide, and is the likely version of the story for newspapers and magazines to quote when they feel a need to refer to Bartley's experience.

Ironically, the final coffin nail was driven into the Bartley story in 1991... ironic because no one seems to have noticed. Edward B. Davis, associate professor of science and history at Messiah College in Grantham, Pennsylvania, did his own research into the story of James Bartley's survival. He queried the Maritime History Archive at Memorial University in St. John's, Newfoundland, Canada, for documents relating to the Star of the East, and received both the captain's full name -- John Killam -- and a complete listing of the crew members that served on board the ship during the fateful year of 1891... and James Bartley's name wasn't on the roster.

Yet still the story is repeated, and people ask if it's true. In the end, some stories will survive, not because they are true, but because many people think they should be.

Anomalies -- the Strange & Unexplained, as well as my other website -- Monsters Here & There -- are supported by patrons, people like you! All new Anomalies articles are now posted for my patrons only, along with exclusive content made just for them. You can become a patron for just $1 a month!

|