1873, October 25 (ca.): Theophilus Picot and the Giant Squid

On or around October 25, 1873, an event occurred which proved, once and for all, that giant squids existed; and as this event was reported to the world at large the story of the discovery was warped by old beliefs, mis-reporting, and more than a little ego, ending with one of the boldest scientific frauds ever... but let's start at the beginning.

On October 29, an article from a Canadian source was published and very quickly picked up by newspapers at least throughout North America... and eventually spread worldwide. The story was titled "A Green-Eyed Monster: The Devil-Fish Seen Off the Coast of Newfoundland," and it explained that two days previous two fishermen in Conception Bay had spotted something odd floating in the waters of the bay. Hoping it was something of value, they went to investigate. One of the fishermen poked the object with a boat-hook and, as the author of this account describes next:

"...suddenly the dark heap became animated, and opened out like a huge umbrella without a handle, and the horror-stricken fishermen beheld a face full of intelligence, but also of ferocity, and a pair of ghastly green eyes glaring at them, its huge, parrot-like beak seeming to open with a savage and malignant purpose. The men were petrified with terror, and for a moment so fascinated with the horrible sight that they were powerless."

As you can see, the author of the article wanted to be a novelist. The article goes on to describe how the giant squid shot a "corpse-like" tentacle across the top of the fishermens' boat "to drag it to destruction." One of the two men had the presence of mind to strike with an axe and sever the tentacle; and the animal then disappeared under the surface, never to be seen again.

The tentacle thus acquired by the fishermen was being kept in the city of St. John's (now just St. John). The article's author had just examined the limb, and described it as 19 feet long and about as thick as a man's wrist. The fishermen stated that they left at least 6 feet of the tentacle on the animal; but the article's author insisted that, from the fishermens' description, he estimated this was closer to ten feet... so he states the actual length of the tentacle would have been 29 feet from beast to end. The fishermen said the body of the animal was forty feet in length; but the author wrote that "the account of the fishermen in regard to the size of the fish is hardly reliable, as they were sorely frightened." The author then mentions that he or she made a suggestion about preserving the specimen in 'spirits,' and that it would be placed in the local St. John's Museum. Then, rather greedily, adds "If we could only get the body what a keen competition there would be for it between the Smithsonian Institution, Agassiz, and Barnum!"

The whole matter could have been written off as just another newsman's invention to fill copy, given how spectacular the presentation was... except that the event actually happened, if not quite in the way it had been described.

Cooler Heads

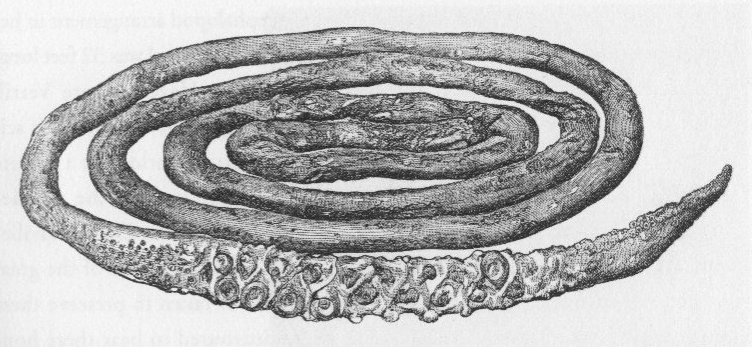

On November 10, 1873, Alex Murray, a representative of the Canadian Geological Survey living in St. John's, Newfoundland, sent a letter about the matter above to a Prof. Jules Marcou with the request that it be put into the hands of Prof. Louis Agassiz, in the United States... and the letter included not only a photograph of the tentacle (illustrated in the woodblock below), it also included specimens of suckers cut from the tentacle. In 1873, giant squids were largely considered mythical beasts by people worldwide, simply a tale that had grown over time with re-tellings. The reason Murray wanted his letter to reach Prof. Agassiz is because Agassiz was the single best-known and respected zoologist in the English-speaking world; if he could be convinced that Murray had evidence of a giant squid, then Agassiz's word would convince everyone else.

According to Murray's letter, on or about October 25, 1873, a fisherman name Theophilus Picot was in a small boat off the eastern end of "Great Bull Island" in Conception Bay on the southeast corner of Newfoundland, Canada, when he spotted something unusual in the waters. However, allow me to quickly note that there is no island named "Great Bull" or "Bull" in Conception Bay... It's likely Murray meant "Bell Island," as it is sometimes called "Great Bell" and there is also a "Little Bell Island" in the bay. On with the story.

Picot spotted a large floating object at a distance from him that he at first took to be either a sail or some debris of a shipwreck. Picot moved closer; as he approached, he could see that the object was clearly alive. Out of curiosity he pulled up alongside the strange object and, according to Murray, struck the object with either an oar or a boat-hook; and the squid -- for that's what it was -- attacked in response. The squid's beak bit at the bottom of Picot's boat and then the animal threw a couple of tentacles across the top of the boat. Picot chopped at the tentacles with an axe, severing at least one. The squid then shot off backwards, "after the manner of squids," leaving a tremendous patch of inky water behind it. Picot could see the creature for some time as it swam away, it's pointed "tail" held up out of the water as it proceeded, its skin the same pale pinkish seen in more common squid.

Picot had estimated the length of the squid as about sixty feet in comparison to his twenty foot long boat, and also stated the creature's beak was "about the size of a six galleon keg." The severed tentacle was brought back as evidence of the encounter by Picot, and this measured 25 feet in length... Picot felt that he had cut it off about ten feet from the main body, implying the tentacle was 35 feet in length when intact!

Illustration of the severed tentacle, made from a photo [larger version here]

Illustration of the severed tentacle, made from a photo [larger version here]

Murray had the good fortune of acquiring the tentacle from Picot, so was able to closely examine and photograph it. Six feet had been cut off the stump end of the tentacle when it first reached land (no reason is ever given), so the remaining portion was nineteen feet; this had been preserved by soaking in brine, which had slightly shrunk the total length down to just seventeen feet by the time Murray examined it on October 31st, six days after the encounter. Murray then sent a copy of the photograph -- which the illustration above was made after -- along with specimens of the suckers from the tentacle with his letter to Prof. Agassiz in the United States.

Murray expressed in his letter that he felt Picot's estimate of the animal's size -- sixty feet -- was likely an exaggeration; but on the other hand, Murray also expressed his belief that the squid might have dragged the boat to the bottom had Picot not severed the tentacle. It's interesting to note then, that the first report of this encounter from someone considered to be an unbiased person of scientific mind -- Murray was a geologist -- suffered both from an assumption that the actual observer had to be wrong about the animal's large size, and the further assumption that tales of giant squid sinking ships was likely true... despite Murray's attempt to minimize the reported size of the squid.

Once Again, Only Different

On November 12, two days after Murray sent off his letter, the Rev. Moses Harvey -- who also lived in St. John's, Newfoundland, and was a frequent contributor to local newspapers and magazines on a variety of subjects -- sent his own letter regarding Picot's encounter to Sir William Dawson of McGill University in Montreal, Canada (presumably... I'll explain later). It's clear from what I've seen that Harvey and Murray were both interested in the tentacle and knew each other; it's unclear if they were associated before the tentacle arrived as a mutual object of curiosity, but both men seem to have had the same access to the unusual find.

In this letter Harvey's account of the event gives less actual detail than Murray did, and it varies from Murray's account in several ways. We are told the event happened on October 26 (not 25), that there were two fishermen in the boat (not just one) and Harvey does not give the name for either man. He states that the men took two arms off the animal, and that one was eaten by dogs after it came ashore; an unnamed clergyman supposedly told Harvey later that the limb was ten inches across and six feet long. As far as the surviving tentacle, we are told that Harvey himself "took measures to have it preserved." After this, Harvey states that both he and Murray then "examined it carefully, had it photographed, and immersed in alcohol," after which the tentacle was placed in the St. John's Museum.

I found a copy of Harvey's letter in The Annals and Magazine of Natural History for January 1874, from London, England. The magazine states that Harvey's letter was addressed to "Principal Dawson," who was likely Sir William Dawson of McGill University, for this very man was mentioned again by Harvey in another article on the same matter written at a later date, where Dawson is referred to as a personal friend. This copy of Harvey's letter claims to have been accompanied by a photograph of the tentacle and samples of the suckers, just as Murray had sent to Prof. Agassiz in the United States.

There is a very strange feel to this letter... much of the description of the specimen and other incidental information mentioned by Harvey closely mirrors the letter sent to Prof. Agassiz by Murray a couple of days earlier; it seems likely that if the two men were working together, that Harvey may have read the letter from Murray before it was sent out.

A further strangeness comes from something you don't know yet: Rev. Moses Harvey, it turns out, is also the author of the "Green-Eyed Monster" article that hit newspapers on October 29. This article, if you'll recall, said the event happened just two days earlier, implying a date of October 27... not the 26th, as Harvey states about two weeks later in his letter. Perhaps he changed the date to better match the October 25 date reported by Murray in his letter. In both the article and his letter, Harvey stated there were two men on the boat and gives no names. It's only in this later letter by Harvey that a second, shorter squid arm is claimed to have been brought ashore and destroyed by dogs... his initial 'Green-Eyed Monster' stated there was only one tentacle. In Murray's letter, much more detail was given of both the encounter and the the examination of the tentacle... and only Murray names the fisherman involved in the matter, solely, Theophilus Picot. Given the details Murray goes into, it is odd that he would fail to mention a second man on the boat, or the existence of a whole second limb from the giant squid, details that Harvey wrote about.

On December 13, 1873, the English magazine The Field contained an article about Picot's adventure, said to be "a notice of the occurrence described by Mr. Harvey, communicated by Mr. T. G. B. Lloyd, who received his information from Mr. A. Murray, Provincial Geological Surveyor of Newfoundland." The Field was sent a photograph of the tentacle by Murray, from which the woodblock print above was made and displayed in that issue of the magazine... all of which implies that Murray was in charge of the actual specimen. Now, remember that for a moment.

The Second Encounter

Sometime shortly after December 2, Alex Murray found himself sending another letter to Prof. Agassiz; for in November -- presumably sometime after the 12th, when Harvey sent off his letter about Picot's adventure -- a largely intact giant squid was fished out of "Logia Bay" near St. John, Newfoundland... which, I do apologize, requires another quick sidetrack. Murray seemed to have a problem with reporting place names (note what I pointed out about "Bull Island" above). Perhaps he was just writing out how locals were pronouncing the names... for there is no "Logia" bay in Canada. Later writers reporting the event typically identified the bay as "Logie Bay," which is now called "Logy Bay," and which is indeed near St. John in Newfoundland.

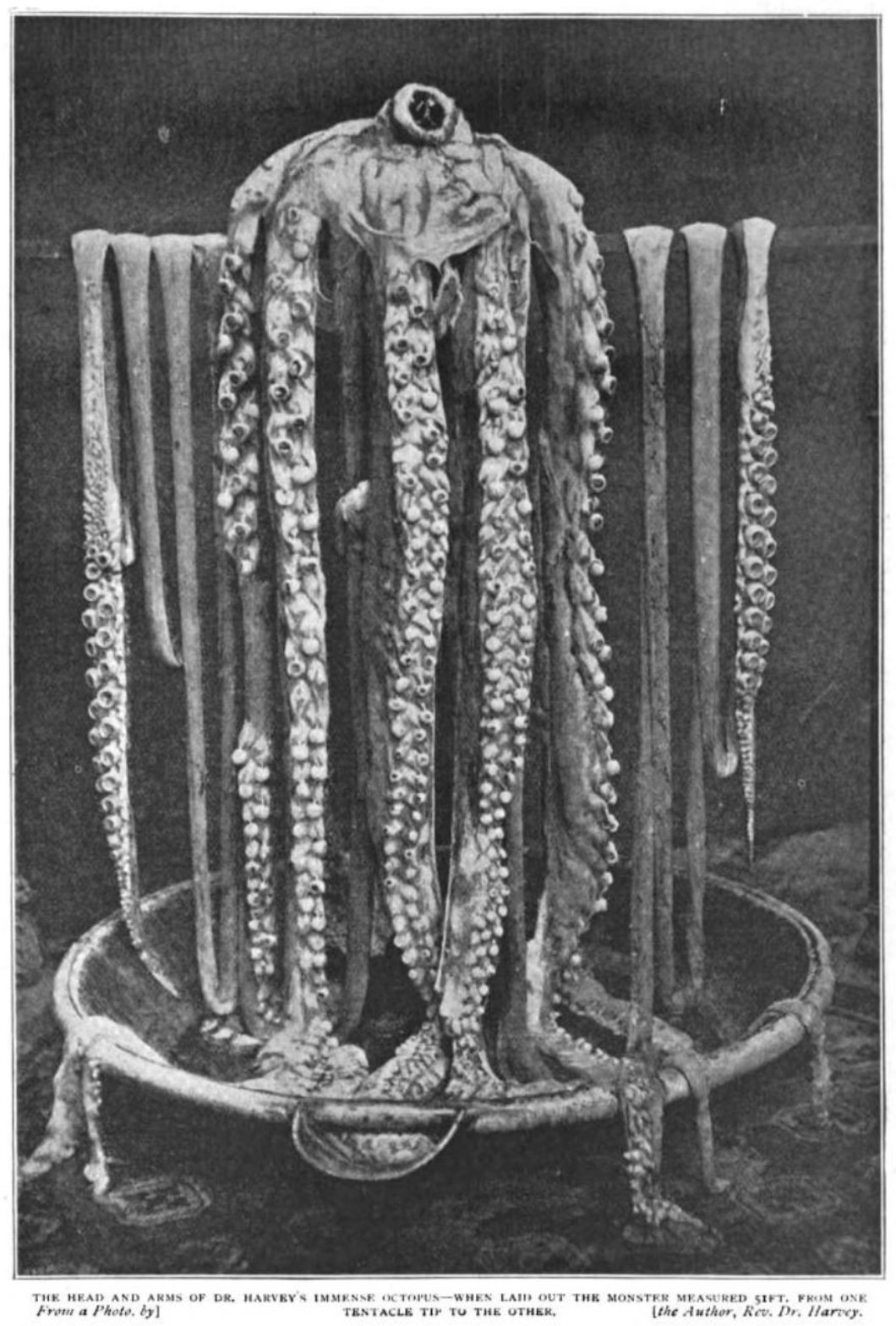

Murray's second letter to Agassiz included two photos (one of which is show below) of the giant squid specimen. The animal had gotten caught up in fishermens' nets, and in being extracted from the nets the animal's carcase had been damaged... most notably, the head was separated from the arms and beak, and the eyes were destroyed. The two large parts remaining, though damaged, still represented the most intact giant squid to fall into the hands of a scientist with the will and means to record the evidence and tell others. The timing was perfect, with news of Picot's adventure still fresh in the hands of Prof. Agassiz, who by now had forwarded Murray's first letter to the Boston Society of Natural History (among other groups). The Boston Society printed the letter in their Proceedings of the Boston Society on November 19, just over a week after the first letter had been sent to Agassiz to start with.

Mouth & arms of the Logy Bay squid [Larger version here.]

The Logy Bay specimen was smaller than the animal encountered by Picot. The two longest tentacles of the animal were twenty-four feet long; combined with Murray's measurement of the head length, the animal was an estimated thirty-one feet long. Murray explained in his letter that the photographs were taken by "Messrs. Parsons and McKenna" from St. John on December 2... which is why I know the letter had to be sent after December 2.

Once again, Agassiz was impressed enough to pass Murray's letters on, this time to the magazine American Naturalist, where both letters were published on February 19, 1874... unfortunately, this publication date came after two problems that altered the public version of the stories. The first of those problems is that Prof. Agassiz died on December 14, just twelve days after the Logy Bay specimen had been photographed; so though Agassiz was able to see and evaluate the evidence and then pass it on, he wasn't around long enough to either get his hands on it or make any public statements about it himself.

The second of those problems was that, simply put, Rev. Moses Harvey felt that he personally owned the new specimen as well as any and all public acclaim that might be garnered from it... and he felt the same in regards to Picot's tentacle.

The Story Grows

On December 20 -- well after Prof. Agassiz received a letter and photos about the Logy Bay specimen, forwarded them to colleagues, and then died -- Harvey's own article about the Logy Bay specimen was printed in the Toronto Globe. Again, it varied from Murray's account; in fact, it varied even from Harvey's own earlier article about Picot's tentacle. Entitled "The Devil Fish," it proved to be every bit as exciting (and questionable) as his "Green-Eyed Monster" article.

The article starts with a reminder that he had written the previous article about the two fishermen in Conception Bay who acquired two arms from a 'Devil Fish' (he had only mentioned one arm in the article he was referencing... did Harvey forget?). Harvey then states "Yesterday a fisherman from Logie bay called on me and informed me that he had captured a devil fish in a net..." which, given the article's publication on December 20, implied the new animal was captured mid-December, not in late November. It also makes clear something Harvey claims many times in the article: that he was contacted first by the fishermen.

Harvey wrote that the squid was captured alive and that, though smaller than the Conception Bay squid, it still took "four stout fishermen" great effort to kill the animal, which they accomplished by cutting its head off while still in the net; and Harvey assures us that "Had it not been entangled in a herring net, so that its huge arms were not available, as it could get no hold by its suckers, the men would have had no chance of capturing it." Past stating the animal was alive and had to be killed when captured -- Murray's second letter implied the animal was already dead when the fishermen began to remove it from the nets -- Harvey also boasts that "Altogether, my specimen is a wonderful sight—a huge cartilaginous tube surmounted with a beak and eyes, but no face," which refutes Murray's statement that the eyes were destroyed when the head was cut off. And do note Harvey's use of the phrase "my specimen," for he states "I am now the possessor of a complete specimen of this remarkable cuttle fish" and "At present it occupies an ignoble position on the floor of an out house, but I am taking measures to have it preserved." Harvey fails completely to mention that Murray examined the specimen, and that it had been photographed at all previous to his article's publication.

Harvey's new article succeeded in getting world-wide attention from newspapers and magazine that reprinted in part and in full both of his two fantastic newspaper articles, factually questionable though they were. In fact, Harvey's claims regarding both specimens became so often repeated that on January 31, 1874, the English magazine The Field -- the same one that ran an article about Picot's tentacle on December 13 -- ran a new article that both described the new Logy Bay specimen (and included a woodcut made after the photo above) and re-presented the story regarding Picot's tentacle with Harvey's changes; in both cases, Harvey was now acknowledged as the man who had saved the specimens for science.

This article from The Field appears to be the version that was most greatly spread about. It combined Harvey's exciting narrative and some of Murray's scientific insights -- without mentioning Murray, of course -- resulting in a single spectacular, but more authoritative sounding, narrative. Harvey was now credited fully with acquiring both the first tentacle and the later body for the St. John's Museum, whether true or not. By May 16, 1874, some zoologists were arguing that Picot's tentacle and the Logy Bay specimen represented unique animals that required a unique Latin biological name; and all of these suggestions ended with "Harveyi," a clear statement of who everyone felt deserved credit, ignoring Murray -- who first reported the events -- and Picot -- who actually fought one of the events!

While this was an overall win for Harvey, there was one detail from Murray's letter that snuck into the account that Harvey probably wasn't thrilled about... the article named Theophilus Picot as the fisherman who cut off the first squid's tentacles.

A Question of Evidence... and Public Relations

Most modern authors on the topic of giant squids now point out that Picot's encounter was just one of a small explosion of giant squid reports that occurred between 1870 and 1876 around Newfoundland, and assert that this unusual number of sightings and encounters is a large part of the reason that scientists of the day finally acknowledged the existence of these beasts... but this is a mistaken take on the situation, which appears to have been first asserted in 1899. By Rev. Moses Harvey.

While it's true that there were many reports of giant squids being seen or found (beached, in nets, etc.) around Newfoundland between 1870-1876, it was not particularly an unusual number. In fact, most biologists that had an interest in such matters already knew that, in general, giant squids did exist. As a matter of fact, Alex Murray mentioned several such events as minor notes in his letters to Agassiz:

- From the first letter: "The Rev. Mr. Gabriel, now residing at Portugal Cove, but who formerly resided at a place called Lamalein, on the south coast of the island, states that, in the winter of 1870 and 1871, two entire cuttle fish were stranded on the beach near that place, which measured respectively forty and forty-seven feet."

- From the second letter: "A very respectable person, by the name of Pike, informs me that he has seen many of these gigantic squids upon the coast of Labrador; and that he measured the body of one eighty feet from beak to tail. He also states, that a certain Mr. Haddon, a school inspector of this place, measured one ninety feet. He tells me, moreover, that the monsters are edible."

In fact, a brief inspection of a list of reported historic encounters and evidence of giant squids -- available in the Wikipedia website [Link Here] -- makes it abundantly clear that plenty of evidence existed previous to Picot's encounter, and on a worldwide basis. So the marine biologists were mainly arguing about exactly what size a giant squid could reach, and how many species there were. This is because they had many reports, but no actual specimens. So the Picot and Logy Bay specimens were important for proving that giant squid could in fact get very big indeed, and in allowing a full inspection of their bodily construction.

For the public at large, however, giant squids were still more or less mythical creatures; and it was the public at large that Harvey's fantastic re-tellings of the events as dangerous squid attacks mostly effected... it was public interest in the stories that elevated Harvey's association with the discoveries. Now, while overall it could be argued that Harvey didn't necessarily intend to take all the credit for these discoveries by writing out Murray and Picot -- after all, it could just be a matter of being in the right place at the right time -- there is some evidence that he liked the attention. Because twenty-six years later Harvey flat out lied to be sure his name was solely associated with the two events.

Rub-a-Dub-Dub

In 1899 -- twenty-six years after Picot's encounter with the giant squid -- Harvey wrote once again about the capture of the tentacle and Logy Bay squid... sort of. The article was published in The Wide World Magazine of March 1899, and Harvey humbly titled it "How I Discovered the Great Devil-Fish." Harvey's retelling in this article changed many major details; and, unfortunately, this is one of the main sources most modern authors use when writing about Picot's encounter. Here's a quick sample:

"My happiness was complete. Fortunately I was well versed in the whole literature of this class of animal; and therefore knew that I had in my possession what all the museums of the world did not contain—a perfect specimen of the gigantic cuttle-fish, commonly named devil-fish, or octopus, of which only some doubtful fragments, widely scattered in various collections, were known to exist. I was thus, by good fortune, the discoverer of a new and remarkable species of fish, the very existence of which had been widely and scornfully denied, and had never been absolutely proved."

...oy.

Harvey's new tale was very different from what was known to have happened. According to Harvey, there were now three people involved in catching Picot's squid, Picot himself (whose name Harvey misspells as 'Piccot'), another sailor named 'Daniel Squires,' and Picot's 12-year-old son, Tom. When the creature was provoked, it grabbed the boat with both a tentacle and a shorter arm, and the boat was actively being dragged under water and in danger of flooding and sinking when young Tom had the presence of mind to take a hatchet and cut off the tentacle and the arm. Upon their return to land, the arm had been left out and eaten by dogs. Tom, told about Harvey's interest in such matters, sought out Harvey at home to tell him the tale and sell him the tentacle. After interviewing the two fishermen -- who were too afraid to go back on the water for days afterward -- Harvey was sure to have the tentacle photographed and given to the St. John's Museum. This, of course, ignores that Alex Murray had been in possession of the tentacle and arranged for its photograph.

Next, Harvey relates how he heard of the capture of a "big squid" in Logy Bay, and how he barely arrived in time to prevent the fishermen from chopping the remains up for use as fertilizer (read that as 'Once again Harvey saves a valuable scientific specimen from ignorant fishermen'). As Harvey tells it, the giant squid was accidentally entangled in the net and tried to attack the fishermen as they reeled it in, forcing them to battle it to protect themselves and their net, which is what resulted in it being severed into two large parts. Harvey then paid the fishermen $10 to deliver the carcase to his house, where he minutely examined it and had it photographed -- only after which he felt he could publish his results, as without a photograph he felt his story would not have been believed. This all, of course, ignores that Alex Murray sent the photos to Agassiz before he died on December 14, and that Harvey's own first account of the matter in the Globe on December 20 did not include photos. Nonetheless, Harvey informs us that he now sent his findings to "a number of scientific men," including in his list none other than: Prof. Agassiz!

Harvey ends this intriguing account of fictional history by stating how he decided to send his specimens to Yale university, and how prominent scientists had suggested naming the species of the specimens either Archeteuthis Harveyi or Megaloteuthis Harveyi... of which Harvey states "I endeavoured to bear these honours meekly."

Harvey also packed the article with examples of his fantastic knowledge of these unusual animals... which on second inspection doesn't display anything more than what was already in print. For example, Harvey states that the normal locomotion of these giant squid is to travel at the surface of the water with their head poking up; he undoubtedly reached this conclusion from Picot's description of how the squid he encountered had escaped. Giant or not, however, squid don't normally float near the surface of the ocean; and the larger the animal, the further out to sea and deeper in the ocean they normally are. So the fact that a giant squid was found floating on the surface so close to land already meant that something was not normal about the animal Picot encountered. I suspect the animal was wounded or dying, and that Picot riled up an already irritated and defensive beast when he struck it. It seems likely that the giant squid had lost control of its buoyancy, or there would be no reason for it to stay at the surface of the ocean as it ran away, as Picot reported.

The Final Question

It's pretty clear that Harvey created a new story that justified his claim to giant squid fame when he published his 1899 article... but did he initially attempt to take credit away from Murray and Picot back in 1873 also? This is a harder matter to answer; but there is evidence that suggests he felt he deserved the credit, and that he might have tried to steal it.

It's true that Harvey was the first in print about Picot's tentacle; but Murray was the man who filled in the details and sent them to the right people. Remember this line from Harvey's "Green-Eyed Monster" article:

"If we could only get the body what a keen competition there would be for it between the Smithsonian Institution, Agassiz, and Barnum!"

The 'Agassiz' mentioned is exactly who Murray sent his fuller report to. Harvey's own letter sent two days later, that both imitated Murray's letter and added a new detail to show he 'knew' more about the matter (the fictional second arm) was sent to a university professor that Harvey personally knew, Sir William Dawson, and who was much closer physically than Agassiz was. Given that Murray sent his letter to Prof. Jules Marcou with the request he hand it to Agassiz, it seems possible that Harvey thought he would get his letter officially recognized before Murray's, beating him to the more prominent publication of 'details.' But Harvey's own letter in this form doesn't appear to have been published until January, 1874... whereas Murray's letter was in print by November, 1873.

Now consider: Alex Murray had examined the Logy Bay squid, knew and named the people who took the pictures of it, and sent a report and copy of the pictures to Prof. Agassiz well before December 14 because Agassiz died on December 14, but had time to pass Murray's second letter and photos on before he died. Meanwhile, the earliest that Harvey can be shown to talk about the Logy Bay specimen is his letter to the Globe, printed on December 20, with no photos (or mention of photos existing). So it appears that Murray knew more and earlier about the Logy Bay squid than Harvey did. Harvey claimed in his 1899 article that he waited to publish his 'findings' until after he had proper photographs taken of the squid to prove it existed... but in reality, Murray sent the photographs off at least a week before Harvey's article about the Logy Bay squid was printed; and Harvey's article at that time didn't mention the existence of photos at all.

Also note that the first two times Harvey wrote about Picot's squid encounter, he stated there were two fishermen instead of one, and did not name the fisherman involved. Picot's name was only added by Harvey when he came back to the topic in his 1899 article. The reason seems to be that, at first, Harvey wanted to obscure the importance of Picot to the acquisition of the tentacle by not naming him and claiming there was more than one fisherman; but later articles that gave Harvey full credit for the find also tended to state that Picot was the name of the fisherman who actually cut the tentacle. So when Harvey wrote his 1899 article to bolster his claim to fame, he couldn't ignore or write Picot out of the story.

Instead, he further increased the people on the boat to three, named them all, and assigned the glorious task of actually cutting tentacles to Picot's young son. Then Harvey claimed Picot and the other adult fisherman were too terrified to put out to sea for several days afterwards, and young Tom -- only 12-years-old -- had planned to use the tentacle as a rope. So by characterizing the finders of the tentacle as fearful, ignorant, and irresponsible, Harvey attempted to show he was a necessary person for the tentacle to actually survive and be appreciated. Oh, and remember that Harvey spelled Picot's name wrong -- 'Piccot' -- throughout the article.

So that's where the matter currently sits. At the moment, history books give Rev. Moses Harvey credit for 'saving' the tentacle and squid of 1873 for the hallowed halls of scientific understanding... but a fuller study of the actual history of the events seems to show him for being just a fame hungry cad, who stole scientific credit from Alex Murray, and actual fame from Theophilus Picot... who remains the only man in history that can claim a one-to-one battle with a giant squid!

Anomalies -- the Strange & Unexplained, as well as my other website -- Monsters Here & There -- are supported by patrons, people like you! All new Anomalies articles are now posted for my patrons only, along with exclusive content made just for them. You can become a patron for just $1 a month!

|