1858, June 20 (pre): Mark Twain’s Prophetic Dream

In 1912, Mark Twain's biographer, Albert Bigelow Paine, described an odd event in the famous writer's life.

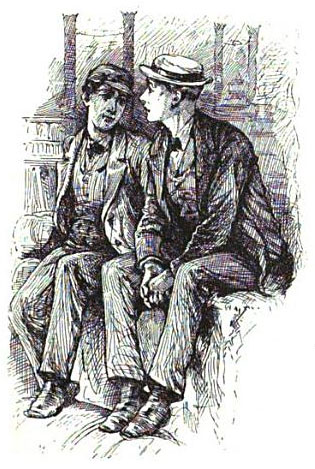

Henry & Samuel Clemens [Picture Sources here]

In 1858, 23 year old Samuel Clemens (aka "Mark Twain") was working as steersman on a steamboat called the Pennsylvania and had recently arranged for his younger brother Henry (just 20 years old) to work on the same ship. It was a good time for the Clemens brothers, and Samuel truly enjoyed having his brother work with him. One night, likely in May or early June of the year, the Pennsylvania was in dock at St. Louis, Missouri, and Samuel spent the night at his older sister Pamela's house in town; and he had a very vivid dream.

Samuel was standing in the sitting-room of his sister's house. Across two chairs a metallic coffin was supported; and in it lay Henry, a bouquet of white flowers with a single crimson bloom in the center, on his chest.

Samuel awoke the next morning convinced the dream was real; he arose and dressed, intending to go downstairs to view his brother's corpse... instead, he went out for a morose early morning walk. He was halfway up the block when he realized he had been dreaming. Samuel ran back and rushed into his sister's sitting-room, and was greatly relieved to discover it empty of the vision he had experienced. He told Pamela about the dream, which helped him calm down some.

Soon after, the Pennsylvania sailed to New Orleans, and Samuel stopped worrying about the troubling dream. This was in part because the ship made the trip safely, but also because Samuel had an argument with a pilot named Brown, resulting in a short fight. Brown had been a troublemaker in the past as well, and the Captain decided he would hire a new man at St. Louis on their way back from New Orleans and let Brown go. To try and prevent further trouble until then, Samuel volunteered to follow on a different ship for this part of the journey, and then to resume his job as steersman at St. Louis after Brown had been replaced. And so the Pennsylvania sailed without Samuel Clemens, who followed two days behind it aboard the A.T. Lacey.

This proved to be a fateful decision. The Pennsylvania's boilers exploded on June 13 just past Memphis, Tennessee, sinking the ship and killing 250 people of the estimated 500 passengers and crew outright; more died due to injuries after. Henry had been blown into the river by the initial blast, but had swam back to the ship to help others escape. As a result of either the initial blast or his return, he had been scalded and inhaled steam, scalding his lungs as well. Samuel was by Henry's side as soon as possible, but nothing could be done... Henry lingered until June 20, when he passed away in his sleep.

Samuel was near destroyed, and the grief of his brother's death and the exhaustion of tending to him for the days after the explosion left him in a sad and dreamlike state; he was taken to the home of a Memphis citizen and given a bed, where he collapsed for the next several hours. When he arose, he mechanically dressed and then went to seek where his brother was lying. The coffin was supported by two chairs; and, though other victims had plain wood coffins, a special fund had been raised for Henry in light of his youth and bravery... so he lay in a metal coffin. As Samuel stood looking at his young brother's corpse, an elderly lady entered the room and placed a bouquet of flowers on his chest; it was all white, except for one crimson bloom in the center.

Many authors now agree that this experience is what led Samuel Clemens to become a member of the American branch of the Society for Psychical Research.

The One Difficulty

Though often repeated now, it must be noted that the account of Samuel Clemens/Mark Twain's prophetic dream about his brother's death has no published existence previous to Albert Bigelow Paine's 1912 biography of the famous author, published two years after Twain's own death. The story of how Henry died is correct, because Paine essentially copied the details of this event straight from Mark Twain's own account of it in his 1883 auto-biographical book, Life on the Mississippi. However, the framework of the initial prophetic dream, and the matching death scene following, both first appear in Paine's 1912 biography.

Mark Twain never wrote an account of this event, though he often wrote or spoke of Henry. This includes all of Twain's transactions with the Society for Psychical Research. In point of fact, Mark Twain's only interest in the Society for Psychical Research (the SPR) appears to be in relation to his own theories regarding telepathy as an explanation for why multiple writers often have the same idea at the same time (which are a set of accounts that I will add to Anomalies at a later time). I've done quite a bit of digging on this matter. None of the records with the SPR reference Twain's dream of his brother's death, and this includes transcripts of spirit communication supposedly made by Twain after his own death.

So the sole source for this story is Albert Bigelow Paine, who uses his book's supposed association with Mark Twain to add authority to the account... but anyone who could have questioned or disputed the story was dead when it was published. Paine claimed to have worked for six years on the biography, so he started four years before Twain's death; so could Paine have worked directly with Twain and heard the story from the author himself? Paine's own biography argues strongly against this possibility in two ways.

First, in the acknowledgements of the first volume of the biography -- the same volume containing the story of the dream -- Paine thanks all the old associates of Mark Twain who shared their experiences and memories with him... but not Twain himself, implying that he did not meet the author, but was relying on the outside sources to form his biography.

Second, in his preface to the same book, Paine makes clear that he himself didn't trust Twain to either tell him the truth or fully remember it, quoting Twain on the matter directly: "When I was younger I could remember anything, whether it happened or not, but I am getting old, and soon I shall remember only the latter." Paine then assures readers that where his biography may be at odds with some things Twain had written about his own life, that he, Paine, "obtained his data from direct and positive sources: letters, diaries, accountbooks, or other immediate memoranda; also from the concurring testimony of eye-witnesses, supported by a unity of circumstance and conditions, and not from hearsay or vagrant printed items." So Paine not only didn't talk to Mark Twain in writing the biography, he further asserted he was more correct about Twain's life than Twain was.

Which means we are left to assume that Paine got the story of the dream from sources other than Mark Twain or his sister Pamela (who died in 1904), when presumably no one else knew the story. Paine may have found the story in a written source such as a diary entry or letter, or been told of it by one of Twain's friends or family members. However, Paine did not state what his source for the dream story was, although he did often state where he got many other details in the biography... which makes leaving out sources for a story that requires more proof a suspicious flaw.

In the end, then, the authenticity of the story of Mark Twain's prophetic dream rests entirely on whether or not you individually choose to trust Albert Bigelow Paine.

Anomalies -- the Strange & Unexplained, as well as my other website -- Monsters Here & There -- are supported by patrons, people like you! All new Anomalies articles are now posted for my patrons only, along with exclusive content made just for them. You can become a patron for just $1 a month!

|