1867 (pub): Vasilissa the Fair

The following Russian folk-tale was first presented in English by William Ralston Shedden Ralston in 1880:

In a certain kingdom there lived a merchant. Twelve years did he live as a married man, but he had only one child, Vasilissa the Fair. When her mother died, the girl was eight years old. And on her deathbed the merchant's wife called her little daughter to her, took out from under the bed-clothes a doll, gave it to her, and said, "Listen, Vasilissa, dear; remember and obey these last words of mine. I am going to die. And now, together with my parental blessing, I bequeath to you this doll. Keep it always by you, and never show it to anybody; and whenever any misfortune comes upon you, give the doll food, and ask its advice. When it has fed, it will tell you a cure for your troubles." Then the mother kissed her child and died.

After his wife's death, the merchant mourned for her a befitting time, and then began to consider about marrying again. He was a man of means. It wasn't a question with him of girls (with dowries); more than all others, a certain widow took his fancy. She was middle-aged, and had a couple of daughters of her own just about the same age as Vasilissa. She must needs be both a good housekeeper and an experienced mother.

Well, the merchant married the widow, but he had deceived himself, for he did not find in her a kind mother for his Vasilissa. Vasilissa was the prettiest girl* in all the village; but her step-mother and step-sisters were jealous of her beauty, and tormented her with every possible sort of toil, in order that she might grow thin from over-work, and be tanned by the sun and the wind. Her life was made a burden to her! Vasilissa bore everything with resignation, and every day grew plumper and prettier, while the step-mother and her daughters lost flesh and fell off in appearance from the effects of their own spite, notwithstanding that they always sat with folded hands like fine ladies. [*The first krasavitsa or beauty.]

But how did that come about? Why, it was her doll that helped Vasilissa. If it hadn't been for it, however could the girl have got through all her work? And therefore it was that Vasilissa would never eat all her share of a meal, but always kept the most delicate morsel for her doll; and at night, when all were at rest, she would shut herself up in the narrow chamber* in which she slept, and feast her doll, saying**the while:

"There, dolly, feed; help me in my need! I live in my father's house, but never know what pleasure is; my evil step-mother tries to drive me out of the white world; teach me how to keep alive, and what I ought to do."

[*Chuianchik. The chulan is a kind of closet, generally used as a storeroom for provisions, &c. **Prigovarivaya, the word generally used to express the action of a person who utters a charm accompanied by a gesture of the hand or finger.]

Then the doll would eat, and afterwards give her advice, and comfort her in her sorrow, and next day it would do all Vasilissa's work for her. She had only to take her ease in a shady place and pluck flowers, and yet all her work was done in good time; the beds were weeded, and the pails were filled, and the cabbages were watered, and the stove was heated. Moreover, the doll showed Vasilissa herbs which prevented her from getting sunburnt. Happily did she and her doll live together.

Several years went by. Vasilissa grew up and became old enough to be married.* All the marriageable young men in the town sent to make an offer to Vasilissa; at her step-mother's daughters not a soul would so much as look. Her step-mother grew even more savage than before, and replied to every suitor—

"We won't let the younger marry before her elders."

[*Became a nevyesta, a word meaning "a marriageble maiden," or "a betrothed girl," or "a bride."]

And after the suitors had been packed off, she used to beat Vasilissa by way of wreaking her spite.

Well, it happened one day that the merchant had to go away from home on business for a long time. Thereupon the step-mother went to live in another house; and near that house was a dense forest, and in a clearing in that forest there stood a hut,* and in the hut there lived a Baba Yaga. She never let any one come near her dwelling, and she ate up people like so many chickens. [*Izbushka, a little izba or cottage.]

Having moved into the new abode, the merchant's wife kept sending her hated Vasilissa into the forest on one pretence or another. But the girl always got home safe and sound; the doll used to show her the way, and never let her go near the Baba Yaga's dwelling.

The autumn season arrived. One evening the step-mother gave out their work to the three girls; one she set to lace-making, another to knitting socks, and the third, Vasilissa, to weaving; and each of them had her allotted amount to do. By-and-bye she put out the lights in the house, leaving only one candle alight where the girls were working, and then she went to bed. The girls worked and worked. Presently the candle wanted snuffing: one of the step-daughters took the snuffers, as if she were going to clear the wick, but instead of doing so, in obedience to her mother's orders, she snuffed the candle out, pretending to do so by accident.

"What shall we do now?" said the girls. "There isn't a spark of fire in the house, and our tasks are not yet done. We must go to the Baba Yaga's for a light!"

"My pins give me light enough," said the one who was making lace. "I shan't go."

"And I shan't go, either," said the one who was knitting socks. "My knitting-needles give me light enough."

"Vasilissa, you must go for the light," they both cried out together; "be off to the Baba Yaga's!''

And they pushed Vasilissa out of the room.

Vasilissa went into her little closet, set before the doll a supper which she had provided beforehand, and said:

"Now, dolly, feed, and listen to my need! I'm sent to the Baba Yaga's for a light. The Baba Yaga will eat me!"

The doll fed, and its eyes began to glow just like a couple of candles.

"Never fear, Vasilissa dear!" it said. "Go where you're sent. Only take care to keep me always by you. As long as I'm with you, no harm will come to you at the Baba Yaga's."

So Vasilissa got ready, put her doll in her pocket, crossed herself, and went out into the thick forest.

As she walks she trembles. Suddenly a horseman gallops by. He is white, and he is dressed in white, under him is a white horse, and the trappings of the horse are white — and the day begins to break.

She goes a little further, and a second rider gallops by. He is red, dressed in red, and sitting on a red horse — and the sun rises.

Vasilissa went on walking all night and all next day. It was only towards the evening that she reached the clearing on which stood the dwelling of the Baba Yaga. The fence around it was made of dead men's bones; on the top of the fence were stuck human skulls with eyes in them; instead of uprights at the gates were men's legs; instead of bolts were arms; instead of a lock was a mouth with sharp teeth.

Vasilissa was frightened out of her wits, and stood still as if rooted to the ground.

Suddenly there rode past another horseman. He was black, dressed all in black, and on a black horse. He galloped up to the Baba Yaga's gate and disappeared, just as if he had sunk through the ground — and night fell. But the darkness did not last long. The eyes of all the skulls on the fence began to shine and the whole clearing became as bright as if it had been midday. Vasilissa shuddered with fear, but stopped where she was, not knowing which way to run.

Soon there was heard in the forest a terrible roar. The trees cracked, the dry leaves rustled; out of the forest came the Baba Yaga, riding in a mortar, urging it on with a pestle, sweeping away her traces with a broom. Up she drove to the gate, stopped short, and, snuffing the air around her, cried :—

"Faugh! Faugh! I smell Russian flesh!* Who's there?" [*"Phu, Phu! there is a Russian smell!" the equivalent of our own "Fee, fast, fum, I smell the blood of an Englishman!"]

Vasilissa went up to the hag in a terrible fright, bowed low before her, and said:—

"It's me, granny. My stepsisters have sent me to you for a light."

"Very good," said the Baba Yaga; "I know them. If you'll stop awhile with me first, and do some work for me, I'll give you a light. But if you won't, I'll eat you!"

Then she turned to the gates, and cried:—

"Ho, thou firm fence of mine, be thou divided! And ye, wide gates of mine, do ye fly open!"

The gates opened, and the Baba Yaga drove in, whistling as she went, and after her followed Vasilissa; and then everything shut to again. When they entered the sitting-room, the Baba Yaga stretched herself out at full length, and said to Vasilissa:

"Fetch out what there is in the oven; I'm hungry."

Vasilissa lighted a splinter* at one of the skulls which were on the fence, and began fetching meat from the oven and setting it before the Baba Yaga; and meat enough had been provided for a dozen people. Then she fetched from the cellar kvass, mead, beer, and wine. The hag ate up everything, drank up everything. All she left for Vasilissa was a few scraps — a crust of bread and a morsel of sucking-pig. Then the Baba Yaga lay down to sleep, saying: —

"When I go out to-morrow morning, mind you cleanse the courtyard, sweep the room, cook the dinner, and get the linen ready. Then go to the corn-bin, take out four quarters of wheat, and clear it of other seed.** And mind you have it all done—if you don't, I shall eat you!" [* Luchina, a deal splinter used instead of a candle. **Chernushka, a sort of wild pea.]

After giving these orders the Baba Yaga began to snore. But Vasilissa set the remnants of the hag's supper before her doll, burst into tears, and said: —

"Now, dolly, feed, listen to my need! The Baba Yaga has set me a heavy task, and threatens to eat me if I don't do it all. Do help me!"

The doll replied:

"Never fear, Vasilissa the Fair! Sup, say your prayers, and go to bed. The morning is wiser than the evening!"

Vasilissa awoke very early, but the Baba Yaga was already up. She looked out of window. The light in the skull's eyes was going out. All of a sudden there appeared the white horseman, and all was light. The Baba Yaga went out into the courtyard and whistled — before her appeared a mortar with a pestle and a broom. The red horseman appeared — the sun rose. The Baba Yaga seated herself in the mortar, and drove out of the courtyard, shooting herself along with the pestle, sweeping away her traces with the broom.

Vasilissa was left alone, so she examined the Baba Yaga's house, wondered at the abundance there was in everything, and remained lost in thought as to which work she ought to take to first. She looked up; all her work was done already. The doll had cleared the wheat to the very last grain.

"Ah, my preserver!" cried Vasilissa, "you've saved me from danger!"

"All you've got to do now is to cook the dinner," answered the doll, slipping into Vasilissa's pocket. "Cook away, in God's name, and then take some rest for your health's sake!"

Towards evening Vasilissa got the table ready, and awaited the Baba Yaga. It began to grow dusky; the black rider appeared for a moment at the gate, and all grew dark. Only the eyes of the skulls sent forth their light. The trees began to crack, the leaves began to rustle, up drove the Baba Yaga. Vasilissa went out to meet her.

"Is everything done?" asks the Yaga.

"Please to look for yourself, granny!" says Vasilissa.

The Baba Yaga examined everything, was vexed that there was nothing to be angry about, and said:

"Well, well! very good!"

Afterwards she cried:

"My trusty servants, zealous friends, grind this my wheat!"

There appeared three pairs of hands, which gathered up the wheat, and carried it out of sight. The Baba Yaga supped, went to bed, and again gave her orders to Vasilissa:

"Do just the same to-morrow as to-day; only besides that take out of the bin the poppy seed that is there, and clean the earth off it grain by grain. Some one or other, you see, has mixed a lot of earth with it out of spite." Having said this, the hag turned to the wall and began to snore, and Vasilissa took to feeding her doll. The doll fed, and then said to her what it had said the day before:

"Pray to God, and go to sleep. The morning is wiser than the evening. All shall be done, Vasilissa dear!"

The next morning the Baba Yaga again drove out of the court yard in her mortar, and Vasilissa and her doll immediately did all the work. The hag returned, looked at everything, and cried, "My trusty servants, zealous friends, press forth oil from the poppy seed!"

Three pairs of hands appeared, gathered up the poppy seed, and bore it out of sight. The Baba Yaga sat down to dinner. She ate, but Vasilissa stood silently by.

"Why don't you speak to me?" said the Baba Yaga; "there you stand like a dumb creature!"

"I didn't dare," answered Vasilissa; "but if you give me leave, I should like to ask you about something."

"Ask away; only it isn't every question that brings good. 'Get much to know, and old soon you'll grow.'"

"I only want to ask you, granny, about something I saw. As I was coming here, I was passed by one riding on a white horse; he was white himself, and dressed in white. Who was he?"

"That was my bright Day!" answered the Baba Yaga.

"Afterwards there passed me another rider, on a red horse; red himself, and all in red clothes. Who was he?"

"That was my red Sun!"* answered the Baba Yaga. [*Krasnoe solnuischke, red (or fair) dear-sun.]

"And who may be the black rider, granny, who passed by me just at your gate?"

"That was my dark Night; they are all trusty servants of mine."

Vasilissa thought of the three pairs of hands, but held her peace.

"Why don't you go on asking?" said the Baba Yaga.

"That's enough for me, granny. You said yourself,? 'Get too much to know, old you'll grow!'"

"It's just as well," said the Baba Yaga, "that you've only asked about what you saw out of doors, not indoors! In my house I hate having dirt carried out of doors;* and as to over-inquisitive people — well, I eat them. Now I'll ask you something. How is it you manage to do the work I set you to do?" [*Equivalent to saying "she liked to wash her dirty linen at home."]

"My mother's blessing assists me," replied Vasilissa.

"Eh! eh! what's that? Get along out of my house, you bless'd daughter. I don't want bless'd people."

She dragged Vasilissa out of the room, pushed her outside the gates, took one of the skulls with blazing eyes from the fence, stuck it on a stick, gave it to her and said:

"Lay hold of that. It's a light you can take to your step-sisters. That's what they sent you here for, I believe."

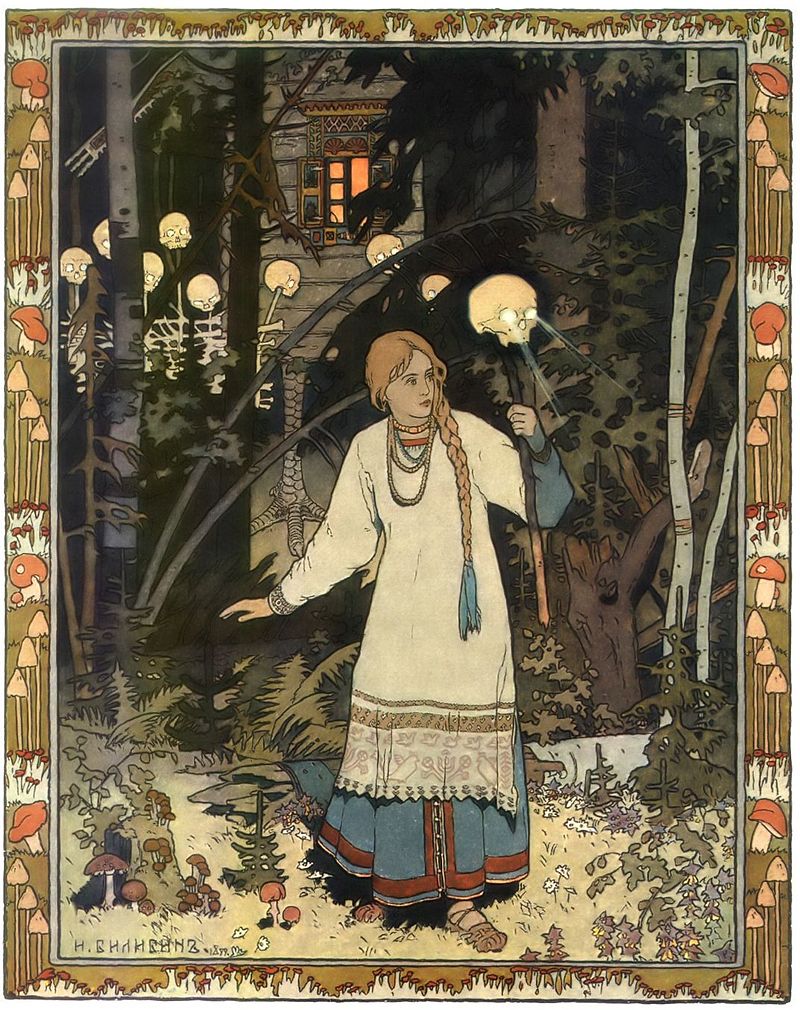

Vasilissa with Skull, by Ivan Bilibin (1902) [Larger version here]

Home went Vasilissa at a run, lit by the skull, which went out only at the approach of the dawn; and at last, on the evening of the second day, she reached home. When she came to the gate, she was going to throw away the skull.

"Surely," thinks she, "they can't be still in want of a light at home." But suddenly a hollow voice issued from the skull, saying:

"Throw me not away. Carry me to your step-mother!"

She looked at her step-mother's house, and not seeing a light in a single window, she determined to take the skull in there with her. For the first time in her life she was cordially received by her step-mother and step-sisters, who told her that from the moment she went away they hadn't had a spark of fire in the house. They couldn't strike a light themselves anyhow, and whenever they brought one in from a neighbor's, it went out as soon as it came into the room.

"Perhaps your light will keep in!" said the step-mother. So they carried the skull into the sitting-room. But the eyes of the skull so glared at the step-mother and her daughters — shot forth such flames! They would fain have hidden themselves, but run where they would, everywhere did the eyes follow after them. By the morning they were utterly burnt to cinders. Only Vasilissa was none the worse.*

[*I break off the narrative at this point, because what follows is inferior in dramatic interest, and I am afraid of diminishing the reader's admiration for one of the best folk-tales I know. But I give an epitome of the remainder:

"Next morning Vasilissa "buried the skull," locked up the house and took up her quarters in a neighboring town. After a time she began to work. Her doll made her a glorious loom, and by the end of the winter she had weaved a quantity of linen so fine that it might be passed like thread through the eye of a needle. In the spring, after it had been bleached, Vasilissa made a present of it to the old woman with whom she lodged. The crone presented it to the king, who ordered it to be made into shirts. But no seamstress could be found to make them up, until the linen was entrusted to Vasilissa. When a dozen shirts were ready, Vasilissa sent them to the king, and as soon as her carrier had started, "she washed herself, and combed her hair, and dressed herself, and sat down at the window." Before long there arrived a messenger demanding her instant appearance at court. And "when she appeared before the royal eyes," the king fell desperately in love with her.

"No, my beauty!" said he, "never will I part with thee; thou shalt be my wife." So he married her; and by-and-by her father returned, and took up his abode with her. "And Vasilissa took the old woman into her service, and as for the doll — to the end of her life she always carried it in her pocket."]

This tale was translated from the Russian folk and fairy tales collection of Alexander Afanasyev, published in eight volumes from 1855-1867. This is from volume iv, and is tale no. 44.

Anomalies -- the Strange & Unexplained, as well as my other website -- Monsters Here & There -- are supported by patrons, people like you! All new Anomalies articles are now posted for my patrons only, along with exclusive content made just for them. You can become a patron for just $1 a month!

|