1504, March 1: Christopher Columbus and the Eclipse

According to current historic accounts, during Christopher Columbus' [1451-1506] fourth voyage to North America -- from 1502 to 1504 -- he had a run of just plain bad luck.

Due to a combination of bad weather, inhospitality, and shipworms, Columbus found himself and his crew stranded on Jamaica in June of 1503 with ships that were no longer seaworthy. Two men were selected to make a dangerous over ocean journey in canoes to the colony of Hispaniola -- 108 miles! -- to try and get help, while Columbus and the rest of his men tried to survive day to day. A barter system had been arranged with the local tribes to get the provisions Columbus' crew needed while they waited for rescue, but some of Columbus' men started stealing from the natives and the relationship soon soured. When a large number of Columbus' men mutinied under the encouragement of a sailor named Porras and took the existing canoes in an attept to go to Hispaniola themselves (which failed), the locals saw this as an opportunity and started to demand greater payment from both Columbus and his crew and the now separate mutineers for the provisions they had been supplying.

To make matters worse, when the two sailors in canoes had reached Hispaniola, the governor there, Obando, stalled when asked for help; you see, he really hated Columbus. So it's said that, facing starvation and an unknown waiting period before help might arrive, Christopher Columbus conceived of a way to save himself and his crew... an idea that has inspired writers ever since.

As recorded in Historie del S. D. Fernando Colombo, written by Columbus' youngest son and first published in 1571, Columbus announced to the Jamaican natives on February 28, 1504, that they had angered the God of the Christians by their inhospitality to himself and his men, and that dire punishments would soon be upon them for this crime. As a sign of their coming doom, Columbus told them, the moon would rise that night "inflamed with wrath."

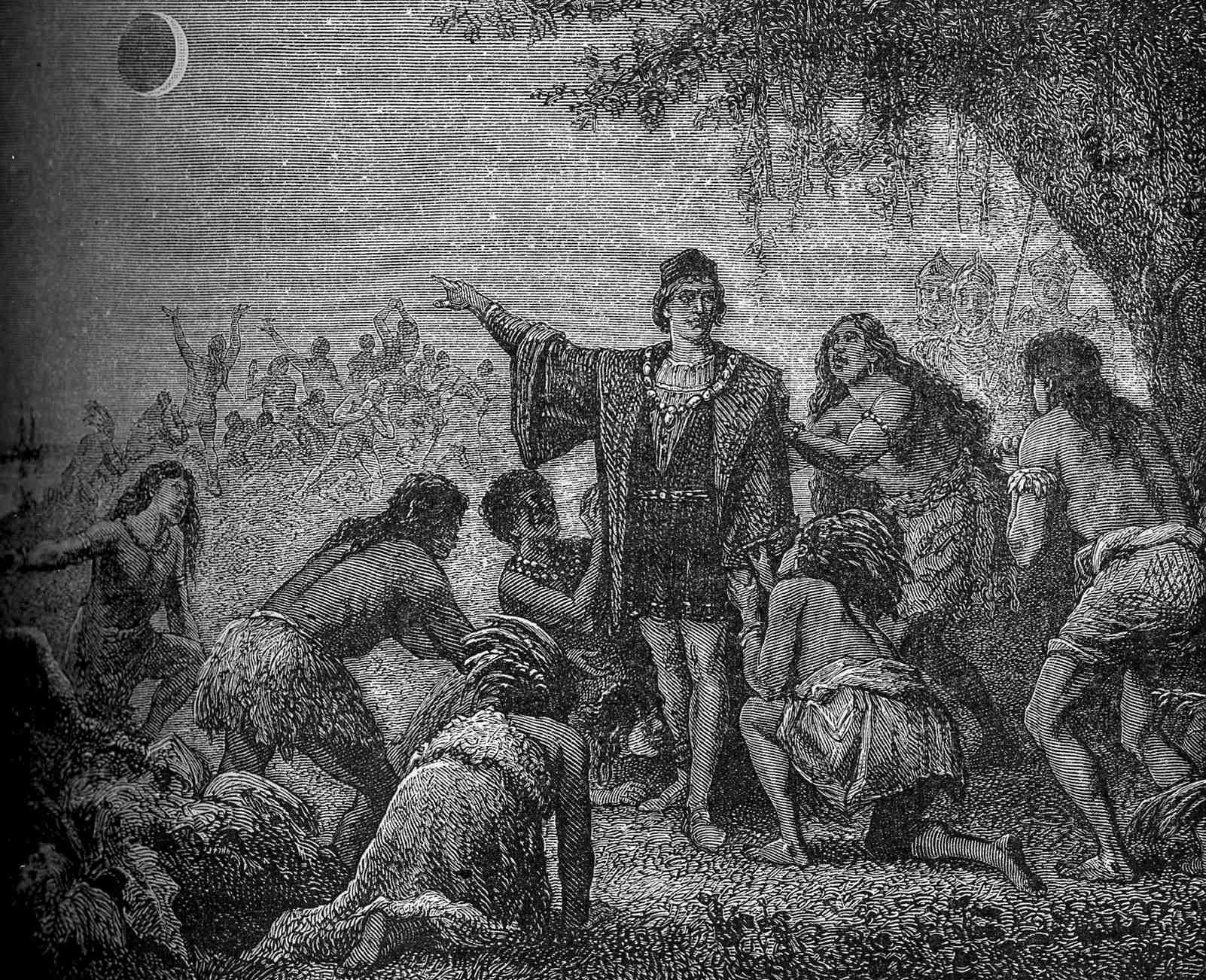

Columbus's Ruse [Larger version here]

Columbus's Ruse [Larger version here]

And, sure enough, when the moon rose that night, it was reddish... and just after midnight, an eclipse began. The now horrified locals showed up with presents and food, and begged Columbus to forgive them and speak to his God to stop the forthcoming punishments. This request he generously accepted and soon enough, as proof of their forgiveness, the moon returned to normal as they watched.

This matter, we are told, inspired the locals with "great veneration for the God of the Christians," and also got the locals to side with Columbus against his mutineers which was "instrumental in the victory gained over the mutineers, their reduction, and the imprisonment of Porras." Columbus had no trouble with the necessary supplies for his and his men's survival from then until help arrived, when one of the two sailors who went to Hispaniola for assistance by-passed the governor by buying a ship and caravel and rescuing Columbus and crew himself.

But, Did It Happen...?

History is not a precise thing, no matter how it may be presented. At its best, the events of the past are attested to by multiple sources dating from the time of an occurrence that can be compared to each other to pull together a consensus report of the most likely way things really happened. But often historians don't have that; what they have is just one person's word for what happened... and they have to decide whether or not to believe that one person. So history is often just stories that have been agreed upon, with no hard evidence past this agreement to support them.

Welcome to one of these historic grey zones.

Much of the early career of Christopher Columbus depends on just one document, a biography written by his youngest son Ferdinand. Ferdinand had actually traveled with his father on the fourth voyage between 1502 to 1504, when Ferdinand was thirteen through fifteen years old... so he's a good person to be reporting about events during that voyage. Except...

Ferdinand wrote the biography when he was around fifty, while compiling documents to combat the fact that the Spanish government at the time was trying to cheat the Columbus family out of the benefits that had been promised to Christopher Columbus before he made his voyages. You see, before the voyages the government promised Columbus rich rewards both socially and financially if he could find something of great value... but once it looked like he actually pulled it off, the government didn't want to share the wealth, so to speak.

After Christopher Columbus' death, an active effort was made by the government to minimize Columbus' importance in the finding of the "New World," and his descendant's found themselves involved in a decades long battle to try and get what had been promised, which they eventually lost. It's quite likely that Ferdinand's biography of his father was prepared secretly at the time with an eye to have it published after Ferdinand's death, as documents that glorified Columbus could have gotten him in big trouble. And in fact, the biography was eventually published because one of Columbus' grandchildren, Luis, was strapped for cash... so he arranged a deal to have it published in Italy in 1571.

All of which means there was motivation for Ferdinand to make his father look like a hero in his presentation of the biography. It's possible, of course, that such temptation did not affect Ferdinand... but we have to be wary of the possibility.

Another point that bothers me: according to Ferdinand, Columbus also used a lunar eclipse on a previous voyage to help determine a time difference between where he was and where he'd started. Now, its not the fact that an eclipse has been used in the same narrative twice that bothers me... it's what Ferdinand mentions happened the day before said previous eclipse. He tells us that Columbus and his men saw a sea monster described as big as a whale with a turtle's shell and two big wings. Which points out one more important thing: historians often pick and choose what parts of reported history will actually be considered history. Obviously, there's been some agreement to not mention that Columbus saw a sea monster; so why was there agreement that Columbus used an eclipse to fool the natives of Jamaica, since it was reported by the same author in the same book? [For more on the sea monster, follow the "See Also" link at the bottom.]

The main reason for such a choice, and the main reason for many choices made in the telling of any country's history, is an attempt to choose stories that not only tell of the founding of said countries, but that also justify that history as moral and inevitable. Consider the tale of Columbus and the natives of Jamaica in this way: it fits a certain type of legend that was very popular with conquerors at the time. The premise is an European tricks native people into doing what the European tells them to, and then into worshiping the European God; after which the story is interpreted to show that the European has demonstrated a moral and mental superiority to the native people, and therefore has not just a right, but a moral duty to rule these poor ignorant people. How else will they learn about God, the Bible, and have a proper life?

It's a self-serving lie, of course, that justifies taking land and wealth from other people. While said legends are often built around true events, they have a tendency to make the central character sound more saintly in each re-telling; and as both a staked claim to the New World, and an attempt to show that Christopher Columbus deserved better, Ferdinand's story is quite suspicious in its neatness. This was ignored by historians however, as the story was used first as a founding myth for the colonization of the New World by Spain, and later as a founding myth for the new country of the United States of America.

As a founding myth for the USA, the tale of Columbus and the eclipse was officially endorsed in 1828 when the American author Washington Irving -- famous for his short story The Legend of Sleepy Hollow -- included the tale in his Life and Adventures of Christopher Columbus, which was soon released in an abridged edition specifically for use in schools. Most modern takes on the tale come from Irving's book. And if you're still not sure about the tale being interpreted as an European displaying superiority over natives, look again at the illustration above, which was published in 1879 and displays a scene completely different from what is actually described in the story... but makes completely clear who's in charge.

So, even though the story of Columbus and the eclipse is considered to be a part of history at this point in time, there has always been some question marks floating over it. However, unless more contemporary sources appear -- such as letters from crew members, or anything else from the right time and place -- the agreed upon story will continue to be considered the historic truth.

Anomalies -- the Strange & Unexplained, as well as my other website -- Monsters Here & There -- are supported by patrons, people like you! All new Anomalies articles are now posted for my patrons only, along with exclusive content made just for them. You can become a patron for just $1 a month!

|